Severe drought in America is nothing new. Water levels at Lake Mead, driver of California’s agricultural engines and provider to much of the American southwest, have declined for 22 years straight. At Hoover Dam, water now sits just 17 odd meters from the shutoff point of 305m where hydropower turbines will shut off and put 8 million people at risk of losing their power. But there is an older drought, one that precedes a time when the infrastructure for Bitcoin consumed more electricity than Finland. This is a drought of political thought.

America has already had its revolution. The founding myth of a country built in a new world relies on something much different than its European counterparts. Daniel J. Boorstin, Librarian to the American Congress (1975-1987) in his essay How Belief in the Existence of an American Theory has Made a Theory Superfluous, wrote about this belief, noting, “Our [American] theory of society is thus conceived as a kind of exoskeleton like the shell of the lobster… we always suppose that the outlines were rigidly drawn in the beginning. Our mission then, is simply demonstrating the truth – or rather the workability- of the original theory.”

In the 18th and 19th centuries, shared history could not build a nation of immigrants. Instead, offered to those settling here, was not the past, but the future, outlined by “Founding Fathers” or “Framers” of the Constitution who proposed a novel republicanism to guide a pluralist nation. Seemingly though, the future has arrived and the “American Experiment” and the Constitution, are now some of the oldest in the world, and yet America still aims to fill its skeleton. Universities with vast departments dedicated to constitutional scholarship come to take the place of political philosophers. Why invent the future when the seed was planted for us? At least that’s the argument.

This historical, as opposed to philosophical view, of political thought in America, has of course been called into question. The rise of critical theory through the second half of the 20th century laid the groundwork for the 1960s, 1990s, and 2010s, where more than ever it seems the structure of power is being, and was, called into question in a society that holds “Anti-Americanism” to be arguably the greatest sin. Occupy wall street, protests against the WTO in Seattle, and marches decrying the Vietnam War and Segregation still stand as the most significant shows of people’s power in recent US memory, voicing concern that the status quo and that exoskeleton used as justification, is not working for the average American, or, more specifically, that the very structures of the American political economy were failing the 99%, black or white.

The great surprise, or tragedy perhaps, of the 21st century then, has been the ability of not the left, but the right, to co-opt this anger, the disillusionment of globalization, economic stagnation, and income inequality to rally their base around the populists, be it in the US or in Britain, who shouted the needs of the many to line the pockets of the few and pretended that America is not and has not always been a home of immigrants, to begin with. But the most significant, most profound of all the effects of the Trump era was the move to “reshore’ industry, de-couple from China, and reinvigorate national industrial policy, a move that has carried over to the Biden administration with the inflation reduction act. For the first time in the post-war era, America, from the top down, is re-evaluating its foreign policy status quo. What come comes next has the chance to change the exoskeleton. This indeed happened before, and semiconductors were still at the forefront even then.

In the 1980s, Southeast Asia, China, and Japan all became economic competitors to the United States. Imports of automobiles, consumables, and electronics came to be a severe threat to hegemony. The 3rd industrial revolution and the Internet age arrived, and the US was unprepared. It would be an unlikely source, in Ronald Regan, to take inspiration from the Asian Tigers’ state-capitalism model all the way to the White House. In 1984, Robert Reich wrote about Regan’s “Secret Industrial Policy”. Counter to the prevailing small government sentiment of the time, Regan recognized the shifting balance of manufacturing power in the world and saw a place for the government to support a transition from manufacturing consumables to high technology. Sound familiar?

His solution was the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which infamously cut rates for top income brackets, but also rescinded tax credits for investment in the old industrial base and preserved those provided for R&D spending. Out with the old, and in with the new. Alongside budget deficits increasing the price of USD, the traditional industry struggled to compete on the world stage, effectively solidifying the import regime of US consumers that persists today. On the other hand, military and weapons development spending increased $400b. Technology, much like the rest of the Reganomics paradigm, would develop from the top down. The deregulation of the finance industry and this military spending was due to create a new technologically adept American economy that bet on innovation instead of the sunset industry.

The result was, of course, the continued offshoring of American manufacturing capacity, where struggling old-guard industrialists moved factories abroad for cheap labor, exasperating inequality, and a financial sector empowered via deregulation to increase public debt. Globalization was not the target of these policies but acted as an influence that pushed Regan to ensure America could stay at the top of the food chain. The renationalization of industry under Trump and Biden then, can be seen as a course correction in a world where US uni-polarity is consistently being re-evaluated. Anti-communism ensured that Regan continued US involvement abroad, in Central America, the Middle East, and South East Asia and this tradeoff, between domestic investment and foreign support, seems to have shaped his industrial policy, a half measure against globalization that continued to bet on US dominance abroad.

Trump and Biden however seem to recognize that the financial center cannot hold. The shrinking value of the US dollar over the past decade harms the purchasing power of Americans shopping for imports, inflation domestically and COVID both evidenced the national security risk posed by global supply chains. So now, while grappling with the same need for structural change as existed 40 years ago, with a chance now to change course, how can re-invigorated national investment avoid the pitfalls of Regan-era industrial policy?

Globalization, although innately tied to economic considerations, has just as much to do with foreign policy and security. The capitalist peace theory, the decreased likelihood of conflict between interconnected economies, has underpinned much of US engagement abroad for the last 50 years, has driven the growth of global supply chains, and caused nearly as much backlash as good. Not only in the developing world, where just last week Niger saw an anti-imperialist revolution, or in eastern Europe where Russia has gone to war against Western encroachment, but in the UK where backlash from globalization and Brexit threatens the stability of the EU, the merits of this system, seem to have been called into question when it’s resulted in increasing inner-country inequality and violent backlash abroad. The winners of globalization are those who can afford to set up shop where there is cheap labor. The inexpensive goods don’t mean much when dollar values fall and incomes remain stagnant.

The success of Biden’s inflation reduction act then depends on his, or the next president’s, ability to take advantage of the pliability of the foreign policy status quo, and a reshaping of how state investment happens. Blackrock, the financial giant that it is, holds a significant role in US state investment, being called in during 2020 to buy corporate stocks to fill the Fed’s balance sheet. Or recently tapped by the US and Zelenski to rebuild Ukraine. Unless state investment decouples itself from the financial center, the US economy will certainly remain hollow. This, of course, was Regan’s grand mistake.

Donald Trump used this in his rhetoric, unifying his base around the idea that globalization has hurt the silent majority of working-class white Americans. Renewed investment in domestic manufacturing certainly creates a healthier economy, but for whom? In his case, Americans worth supporting were the wealthy business owners who simply needed more cash to fund operations, or the white working class. History seems to be repeating itself. Tax cuts abound, and investment funds stay at the top of circulating from New York to Chicago, London to Hong Kong, Palo Alto to Texas Oil Fields

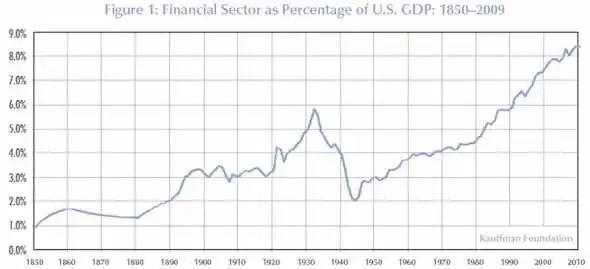

If Biden is to be successful, investment has to reach those Americans for whom globalization took away their industries. Renewed government funding for semiconductors, solar manufacturing, and electric vehicles rely on the idea that America can stay on top of the new green economy, but without a strong middle class of consumers, how will this be the case? It seems that America is stuck in its exoskeleton, betting on innovation from old-school titans like Ford, seeing high-tech manufacturing as the great solution to its ills. Nothing will be materially different until this chart looks different. Real productive power happens outside of finance, where tangible goods are produced.

The image of China as an economic power is not because of its financial centers as much as it is based on the quantity of goods it provides for the US. When China moved to industrialize, its first great misstep was to move agrarians into the cities so they might work in factories, hence the Great Chinese Famine. It was the later choice, to instead industrialize rural areas, which unlocked new productive capacity. How different is this really than an investment through the financial sector which relies on innovation in New York, California, and major metropoles and ignores middle America?

Imagine, for a moment, the prospect of American national investment based on multi-ethnic opportunity and the development of the areas of the United States that were lost due to globalization. Might such investment allow disengagement from the costs of multinational corporate operations, the security apparatus to support them, and the great human suffering that comes in the form of violent conflict whenever that paradigm is questioned?

From Afghanistan to Ukraine, Vietnam to Iraq, the US has lost moral authority as a liberator and harbinger of economic development. Is this not directly tied to an inability of national investment to support America’s own citizens? Is the backlash against these conflicts and the election of Trump not evidence of this fact? Average Americans feel left out by the grand economic game the US is playing.

And so, as we look to rewrite the rules once again, can America live up to its promises? Dis-entanglement has been tried before, and national investment into high technology has been tried before, what can be different this time? Genuine competition is the hope. Investment in the top of the ladder only creates unproductive bloated firms with soft budget constraints, you can ask the Soviets how that went. Capital accumulation is nothing without increased productivity. Without unlocking new capacity in the US, inflation-reduction spending will be for naught.

The US government desperately needs a new way to reach the real drivers of growth, the middle class who spend more of what they make and employ their neighbors. The financial sector is specifically designed to keep money at the top and avoid taxation at all costs. Fees at each step of the way ensure that final capital recipients have razor-thin margins to operate and financiers get paid. There is not much room there for new expenditures, growth, or development to actually improve operations. Maintaining cash flow is put above all else.

When the United States wants to grow semiconductor manufacturing, companies bid for the contract. Of course, there is collusion to increase costs on the front end and limited real growth on the back end. New systems in place to invest at the local level, instead of top-down nationally, and to promote competition from the bottom up might provide a solution, one that not just anarco-syndacalists might be happy about.

Of course, Mark Fisher was spot on in his calculation that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than a systems-level change like this taking place, but this era of transition in the world economy offers an incubator in which something different might be tried. The costs of the status quo have never been more obvious. So now the United States is presented with an opportunity, to clutch fruitlessly onto its foreign holdings, its international manufacturing regime, its military-industrial complex, Ukraine, West Africa, and Taiwan, or to retreat inwards, to fill its exoskeleton, its North American continent, and its flyover country with those riches it made looking outwards when it could afford to. Nothing so ambitious has been tried since the New Deal, but what are the other options considering the circumstances? Re-nationalization is seen as a priority on both sides of the aisle. Will the left be able to ensure the new industry empowers everyone, or have they already forgotten Regan, have they already forgotten Trump? Opportunity abounds, and if history repeats itself, it’s destined to keep everyone exactly where they are, without exception.

[Photo by DWilliam / Pixabay]

Henry Clayton is a recent graduate of the University of the South: Sewanee. He previously wrote about economics for Modern Treatise Magazine before joining Nuveen as a research analyst. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.