In this sixth article among a seven-part study on Afghanistan, Adnan Qaiser, with a distinguished career in the armed forces and international diplomacy, discusses Pakistan’s preoccupation with its adversaries in Afghanistan in the shape of hostile Pashtun presidents, the United States and archrival India. [Read previous parts here]

Instead of becoming a forge that melds neighbours; Kabul has remained an anvil on which Pakistan-Afghan relations keep facing blows one after another.

As discussed in Part-V, Pakistan has not only suffered animosity at the hands of successive Afghan governments but also remained afflicted by America’s fluid strategic interests in the region as well as India’s machinations, as its nemesis.

Thus, during the 19-year-long war Pakistan nervously watched the U.S. strategies failing in Afghanistan as well as India’s ascendency in Kabul owing to New Delhi’s close ties with Tajik, Uzbek and Hazara ethnicities. Although a subject of a separate debate, Islamabad has remained distrustful of Washington’s long-term designs in Afghanistan, which it believed were meant to seize its nuclear assets and defang Pakistan of its nuclear capability. As Pakistan got inundated with C.I.A. operatives and contractors – on the pretext of searching al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden – Islamabad remained caught in the dilemma of fighting the so-called “war on terror” as a “major non-NATO ally” on the one hand, while reining-in the ever-expanding American footprint in the country, on the other hand. The U.S. is reportedly constructing one of its largest embassies in Islamabad similar to the one it built in Iraq.

Rawalpindi (Pakistan’s military headquarters, overseeing Afghan policy) remained convinced about hardly any chances of the U.S.-led NATO forces’ military victory in the “graveyard of empires.” However, its counsel to “stop grandiose plans, get practical,” and seek a political solution in Afghanistan keep falling on deaf ears in Washington and Brussels.

As I had underscored in the last part (Part-V), Islamabad’s support to the Taliban comes out of security compulsions and not from any ideological commonality with the violent, fundamentalist and medieval-looking militia. Thus, following the dictum of “a lesser enemy is a better friend than a greater enemy,” while Pakistan backed the Taliban under duress – Taliban too did not recognize the Durand Line boundary between the two countries during their earlier reign – Islamabad remains wary of the militia’s ties with its anathema, the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), as well as the spill-over effects of Islamization, extremism and violence that keeps Pakistan in docks.

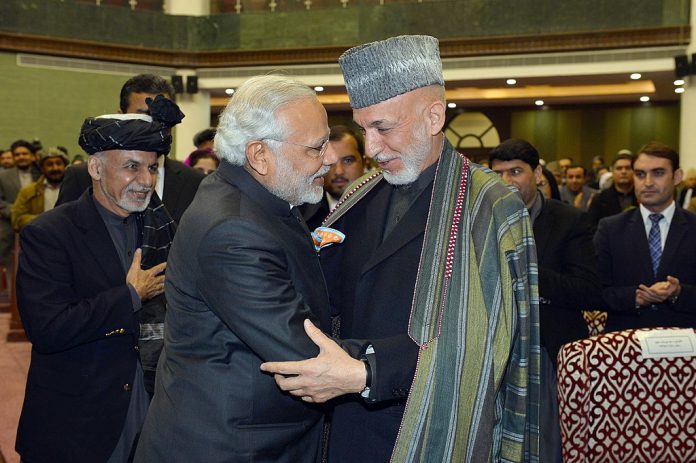

Afghanistan’s “Modern-day Shah Shujas” – Karzai and Ghani

It may sound undiplomatic but from Pakistan’s standpoint, the history first occurred as a tragedy and then repeated as a farce in the presidentships of Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani.

While President Karzai, who became a leader by a stroke of luck at the Bonn Conference in December 2001, remained obstinate and uncompromising towards Pakistan, his successor too remained unsparing in his derogatory onslaught and kept mudslinging Islamabad.

While history would remember President Karzai through his epithet of “Mayor of Kabul;” President Ghani’s sobriquet of a “technocrat foreign-puppet” shall haunt his legacy. However, such appellations, ironically, represent a fractured Afghan polity and a splintered society, fissured on ethnic, linguistic and tribal lines.

Karzai had been a man of contrasting moods. While his utterances were cool and calculated, they often carried venom and spite. Grovelling at the American’s feet one day for his rule’s survival, he went for Washington’s jugular vein the next to establish his nationalist credentials. Chuckling with Islamabad in the morning, the president snarled and sneered against his benefactor in the evening in New Delhi. A man of changing hues with shifting circumstances – or to please his respective audiences – Karzai donned the persona of a democrat, an autocrat and a theocrat simultaneously. A sophisticated feminist in Washington, he acted as a rigid misogynist in Riyadh and turned into a merciless power abuser in Kabul. At the tail end of his tenure, a largely “isolated” President Karzai, who made several enemies during his reign, vainly tried to appear nationalistic to shed his personification of an “American lackey.”

While both the presidents remained wary of signing a strategic pact with the U.S. – and remembered in Afghan history as another Shah Shuja – they gladly inked the accords. Both Pashtun leaders tried to shed their image of former Afghan ruler, Shah Shuja – who was enthroned by the British during the First Anglo-Afghan War – carrying similarities with Karzai’s coronation by the U.S. in 2001 and Washington’s acceptance of Ghani’s twice fraudulent presidential elections.

While President Karzai signed the Strategic Partnership Pact with President Obama on May 1, 2012, he left the Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) to be signed by his successor. Thus, by inking his signatures on the BSA that allowed the U.S. troops to remain stationed in Afghanistan after the end of combat operations on Dec. 31, 2014, Ghani also accepted the moniker of a foreign puppet.

Documenting Karzai’s apprehensions about his legacy, eminent British journalist Christina Lamb records in her epic book, Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan to a More Dangerous World: “So it was all about history. After years of being seen as a puppet of the West, Karzai did not want to be remembered as the ruler who signed for the presence of foreign troops. He was often mocked by the Taliban as a latter-day Shah Shuja, the exiled Afghan ruler who was restored to the throne by the British in 1839 and slaughtered once they left.”

Amid souring of his relations with neighbouring Pakistan, President Karzai’s signing of Security and Trade Agreement with New Delhi on Oct. 4, 2011 added much to Pakistan’s consternation. Despite describing the two countries as “conjoined twins” Pak-Afghan historic mistrust and animosity grew many-fold under Karzai. Historian William Dalrymple called the two countries “enemies since birth” for a reason.

Karzai’s heated exchanges and frequent melt-downs with Pakistan’s president General Pervez Musharraf had been no secret. At one point, Musharraf blamed Karzai for behaving “like an ostrich” and refusing to acknowledge the truth just to shore up his political standing at home. Their trading barbs at each other publicly forced President Bush to invite them at the White House on Sep. 28, 2008 to give an earful. Emphasizing “the need to cooperate, [and] to make sure that people have got a hopeful future” in both countries, President Bush appealed to the bickering presidents to put aside their differences and “strategize together” on how to defeat terrorism.

President Karzai’s verbal brawls with Pakistan’s military leadership remained the order of the day during his rule. At the president’s insistence on delivering Taliban’s emir, Mullah Omar, during a trilateral summit with Iran on Feb. 18, 2012, Pakistan’s former foreign minister, Hina Rabbani Khar had to reproach the demand as “not only unrealistic but preposterous,” emphasising the “need to have some hard talk” with the president.

Karzai’s sudden anti-Pakistan demeanour had in fact surprised the Pakistani authorities. Having lived comfortably in Pakistani cities of Peshawar and Quetta with a thriving family business on Inter-Services Intelligence’s (ISI) stipend during the Afghan jihad and civil-war, the Afghan leader, midwife by the Bonn Agreement of December 2001, remained an irritant for Pakistan Army, inviting frequent reprimands. His undiplomatic and provocative fulminations often incensed Islamabad, calling him the “the biggest impediment to the peace process.” At his snide remark of “external forces acting in the name of Taliban,” an exasperated Islamabad saw him “a joker in the pack … [who was] taking Afghanistan straight to hell.”

A prickly and livid President Ashraf Ghani, on the other hand, kept lambasting Pakistan for allegedly granting the Taliban safe-havens and introducing a new border crossing system in June 2016. The president had been particularly vexed at Islamabad’s border-fencing of the 2336km long Durand Line to stop the infiltration of terrorist TTP into Pakistan. The regulatory transit mechanisms put in place by Islamabad to streamline the flow of Afghan people into Pakistan, running into thousands on daily basis, remains a bone of contention between the two capitals. Kabul’s denial of the Durand Line and its continued protestation at the new border-crossing system led to frequent border closures and fire exchanges between the border-guards of the two countries. Despite a U.S. brokered hotline to settle their bilateral disputes amicably, troops and armour from both sides keep facing off and killing each other intermittently.

Intoxicated with power, the politicians, however, should never forget their dispensability. Similar to the mysterious and untraceable assassinations of leaders like Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in Lebanon and President General Zia-ul-Haq and Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto in Pakistan, politicians must not turn their opponents into enemies. Since life has a strange way of presenting its bill; Karzai and Ghani may too receive their checks with the departure of foreign forces from Afghanistan.

Pakistan-U.S. Divergence and Distrust on Afghanistan

While Kabul and Washington kept blaming the ISI for supporting the Taliban and providing sanctuaries to its supreme leadership council (Quetta Shura) and Haqqani command council, Islamabad safeguarded its strategic interests in Afghanistan. At one stage, a frustrated former Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen designated the Haqqani network as ISI’s “veritable arm.” Islamabad, however, absorbed the criticism patiently and deftly – firmly rejecting the idea of Pakistan becoming a “scapegoat” for failures in Afghanistan. As Washington’s tolerance came to a head, then C.I.A.’s chief, Mike Pompeo warned Islamabad to “destroy safe havens” in Pakistan and Pentagon threatened to take “unilateral steps in areas of divergence.” Islamabad responded by refusing to allow anyone to “fight the Afghan war on Pakistani soil” – a reference to cross-border strikes and hot pursuit attacks.

Pakistan faced an internal dilemma too, when people started seeing Islamabad’s cooperation and intelligence sharing with Washington in the “war-on-terror” as an “American War.” In the aftermath of several incidents the people of Pakistan turned against their ally of past seven decades, with PEW research survey finding anti-Americanism shooting up to 74 percent by June 2012:

1) First of all, despite designated as a “major non-NATO ally” in the war-on-terror in March 2004, Pakistan remained a victim of intensive U.S. drone-strikes. Along with 414 drone-strikes between 2004 and 2018, U.S. forces also carried out at least 24 cross-border attacks in Pakistani territory, causing intense misery, fear and civilian casualties to Pakistan.

2) Then in January 2011, an American contractor, Raymond Davis, working for the C.I.A shot-dead two Pakistani motorcyclists in broad daylight on a crowded road, further straining Pakistan-U.S. relations.

4) Subsequent to Raymond Davis case, the ISI threatened to pull-out of “Tri-Star Intelligence Sharing Pact,” if C.I.A. did not provide it with the whereabouts of 438 U.S. operatives and 1,079 contractors in Pakistan. Enraging the ISI, the American intelligence claimed to have lost them.

5) Later, the U.S. raid to kill Osama bin Laden, which Islamabad claimed to have been carried out without its knowledge or consent in Abbottabad in May 2011, added to further tensions between the two countries.

6) Finally, a cross-border attack by NATO forces at a Pakistani check-post at Salala killed 24 soldiers including two officers on November 26, 2011. Stopping NATO’s Ground Lines of Communication (GLOC) through Pakistan, an infuriated Islamabad called the strike as an “unprovoked, deliberate and pre-planned blatant act of aggression.

While boasting to have arrested over 400 al-Qaeda terrorists on its soil, Islamabad also exaggeratedly claims to have lost some 62,096 innocent lives between 2002 and 2017 and damaged its economy by $123.13 billion in the U.S. war on terror. However, a Brown University’s report found Pakistan to have lost only 23,372 lives and received $33.4 billion as civil and military aid and assistance, including Coalition Support Fund between 2002 and 2016.

Viewing the criticality of Pakistan’s role in the signing of U.S.-Taliban deal, the U.S. CENTCOM chief, General McKenzie admitted Pakistan’s “support has been very important in directing the Taliban to come to negotiations and their continued support is going to be very important [for them to] live up to their commitments.”

Pakistan’s India Distress and Disquiet

Afghanistan’s historic rentier mindset (discussed in Part-III) has made it look towards foreign countries for financial, political, and military support. Despite President Ghani’s vociferous pledge not to allow any proxy war on Afghan soil; Afghanistan remains an arena of regional Buzkashi (goat-grabbing game) owing to its strategic geographical location.

India remains Pakistan’s another bête noire in Afghanistan. Claiming to have a 126km long contiguous border with Afghanistan at Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan area – India keeps offending Pakistan’s sensibilities. Taking a cue from Kautilya, when the Hindu war-strategist (350-283 BCE) defined one of the dictums of his Chankaya doctrine as, “The enemy, however strong he may be, becomes vulnerable to harassment and destruction when he is squeezed between the conqueror and his allies” (Arthashastra, Verse 6.2.40), India has kept Pakistan preoccupied at its western border through successive hostile Afghan governments, when their intelligence agencies overlooked India’s subversive activities in Pakistan by proxies.

In his scholarship My Enemy’s Enemy: India in Afghanistan from the Soviet Invasion to the US Withdrawal, Avinash Paliwal gives a detailed account of how India has been exploiting its longstanding ties and strategic interests in Afghanistan to destabilize Pakistan.

Quoting India’s former foreign secretary Lalit Mansingh, Paliwal gives New Delhi’s Islamabad outlook and admission: “As Pakistan increasingly became our problem, Afghanistan emerged as kind of a counter-balance. To keep Pakistan on its toes, friendly relations with Afghanistan, which always created a kind of anxiety in Pakistan, were kept up.”

Bringing into focus the endgame and a new great game that surround the geopolitics in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India; historian William Darymple has already warned of the “danger of an escalating conflict between the two nuclear powers that could threaten the world peace.” Even former U.S. Defence Secretary Chuck Hagel had noted in 2011: “India has always used Afghanistan as a second front. And India has over the years financed problems for Pakistan on that side of the border. And you can carry that into many dimensions.”

As Afghanistan that has long remained at war against itself keeps portraying a glum spectacle of violence, infighting, corruption, ineptitude, soliciting international aid for survival and recognition for legitimacy; its continued acrimony and distrust against neighbouring Pakistan adds to Afghan instability.

Pakistan’s regional dilemma lies in the indictment made by Richard Holbrooke. Blaming Islamabad for all the ills of Kabul, the former U.S. special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan had noted, “We may be fighting the wrong enemy in the wrong country.”

However, since good sentiments do not make good policies, Islamabad’s strategic interests, especially its American distrust and India’s detestation obliges Pakistan to “keep its friends close; but its enemies closer.” Thus, Pakistan could never let Afghanistan slip into the hands of its rivals and adversaries. Pakistan’s civil and military officials carry a firm belief that having suffered at the hands of wars and civil wars in Afghanistan for the past four decades, they have earned the right to hold Kabul’s strings.

As mentioned in Part-V, Islamabad has patiently seen its Afghan policy’s success, trusting the victory may be late in arriving; it will not be denied. Having been instrumental as a frontline state in defeating two superpowers on Afghan soil – first as an adversary and second as an ally – Pakistan knows it has the wherewithal to hurt, where its pains.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

The authoris a political and defence analyst with a distinguished career in the armed forces, international diplomacy and geopolitical research. He can be reached at [email protected].