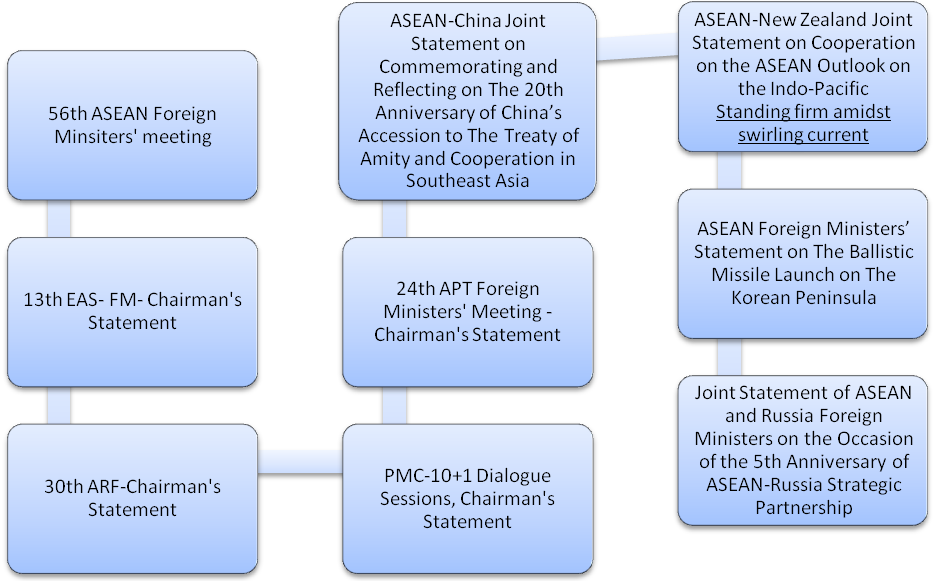

The week of mid-July has been eventful and captivating for ASEAN-watchers, with several significant meetings taking place. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) hosted a series of meetings, including the 56th ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, 13th East Asia Summit (EAS) Foreign Ministers Meeting, 24th ASEAN Plus Three (APT) Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, ASEAN Post Ministerial Conference (PMC 10+1) Sessions with Dialogue Partners, trilateral meetings, and the 30th ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) meeting in July 2023. As a result of these events, ASEAN released nine statements, comprising four bilateral statements with dialogue partners, four Chairman’s statements, and one joint communiqué. For details, see Figure 1. Indonesia is currently chairing ASEAN, and all the Chairman’s statements and the Foreign Ministers’ Joint Communiqué share commonalities in various areas, including ASEAN Community Building, ASEAN’s role as an epicenter of growth, the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, ‘connecting connectivities,’ sub-regional cooperation, development and dialogue with partners, and regional security concerns.

The strategic breakdown of these extensive subjects sheds light on ASEAN’s approach to regional and international issues and its ongoing efforts to position itself at the heart of Southeast Asian regional affairs. This consistent outlook reflects ASEAN’s commitment to shaping the regional security architecture. While delving into each aspect within the confines of a commentary is challenging, this write-up aims to explore and comprehend ASEAN’s official stance on Myanmar.

The Situation in Myanmar

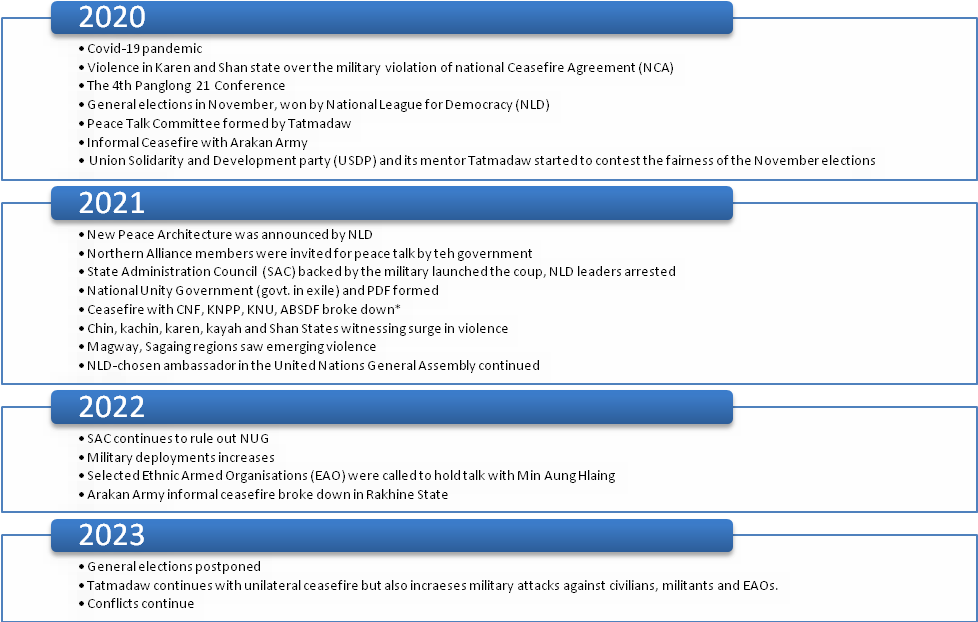

After the February 2021 military coup in Myanmar, the country’s decades-old history of military oppression, poverty, ethnic conflicts and economic turmoil have only increased. The military ousted the elected government in the last coup which has then forced the National League for Democracy (NLD) leaders to form a government in-exile in the name of National Unity Government (NUG). Since then the country has been witnessing resurgence in the anti-military confrontations and civilian unrest in order to bring back democracy. These uprisings are not unified, somehow fragmented and the complex ethno-social-political structure of Myanmar has contributed to the further deterioration of the overall situation in Myanmar in the recent past. However, one needs to remember that even before the February coup; the ethnic conflicts in Myanmar were prevalent. In simple words, the Karen National Liberation Army was fighting in Kayin State, the Kachin Independence Army was mostly prevalent in Kachin State, and the Shan State Army was predominant in Shan State. The other minorities were fighting in their respective areas as well. Yangon along with other cities and states of Myanmar has also witnessed the 8888 uprising, the Saffron Revolution of 2007 and the repeated atrocities against the Rohingya Muslims. Before Myanmar could reasonably recover from this chaotic situation followed by the 2015 elections, the country slipped deep inside the darkness of immoral and unethical governance and government once again by the February coup. The Myanmar experts however could sense a failure in Suu Kyi’s governance and government as well. In 2016-17 also, for instance, brutal carnage against the Rohingyas forced these people to flee from their places leading to massive internal displacement and refugee outflows. The government of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi tried to hide in silence and pushed the dust under the carpet. She also portrayed an image of blending between NLD and the military leaders in the country. This image however, proved to be a deception and the February 2021 coup has only worsened and multiplied the existing vulnerable security situation in Myanmar. Post the February coup, the common people in Myanmar have started to agitate against the military rule as they did not prefer going back to the grey days of Junta rule. NUG’s armed wing- People’s Defence Forces (PDF) now has around 65,000 recruits who are fighting actively against the military of Myanmar. Many of the PDF units have coordination with the Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs). According to some estimates, 40%-50% of the country’s territory is now controlled by the PDFs and EAOs. Most of it is located in the less-populated outskirts of the country whereas the military still holds a strong grip on the population centers. To gain control over the less-populated jungles and outskirts, the Myanmar military has started aerial bombing on the pockets of the PDFs and EAOs causing harsh injuries and death to the human lives and damage to the infrastructure. Myanmar’s army rulers have pushed the due election multiple times with no signs of hope in the near future. Refer to Figure 2 for the recent ethno-political developments in Myanmar in the last four years.

A Conscious but Divided ASEAN Identity

The impact of this extremely volatile situation inside Myanmar has caused trouble for most of its neighbors including the ASEAN members. The problems include cross-border illegal migration, human trafficking, trafficking of narcotics and arms, trans-border insurgency, unrest in border areas and so on. ASEAN and its dialogue partners are deeply concerned with these issues and their effect on their national interests. The February coup in Myanmar has legitimately raised alarm for the regional security and as a result, the ASEAN has become more conscious of its identity as an epicenter of growth in Southeast Asia. The security turmoil in Myanmar and its fallouts have thrown challenges to the concepts like ASEAN Centrality and ASEAN Way. The more ASEAN’s credibility and efficiency to understand and manage a conflict within the territory of its member country has come under critical lenses, the more it has become regular on discussing Myanmar to show vigilance and genuine willingness to patch up the mess. For the past few months, post the February coup, ASEAN squeezed Myanmar’s right to participate in its events; only to be broken by Thailand as it hosted an informal meeting with all ASEAN foreign ministers (including Myanmar) to discuss the Myanmar peace process on June 18-19; 2023. Thai Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai sent the invite to his ASEAN counterparts to ‘fully re-engage’ the generals of Myanmar. While Indonesia declined this invite, Malaysia cited prior commitment of its foreign minister, Cambodia sent its Deputy Foreign Minister to attend the meeting. An incident like this only embarrassed the core mantra of ASEAN as a regional organization and its divided attitude was evident. The foreign minister of Myanmar also attended the MGC and BIMSTEC meetings in Bangkok just after the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ meeting and PMC on July 16-17. This time, the Indian Foreign Minister, Dr. S. Jaishankar also met the Myanmar minister and discussed strategic connectivity projects like India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway and its early completion.

The Official Position of ASEAN on Myanmar

(1) The statements released after the latest round of ASEAN foreign ministers meeting, PMC, EAS Foreign Ministers’ meeting, APT Foreign Ministers’ meeting and ARF meeting, have “reaffirmed” ASEAN’s and its partners’ position on the Five-Point Consensus (5PC) to remain a main reference to address the political crisis in Myanmar. These statements condemn the violence, air strikes, sabotage to the public infrastructure, and call for inclusive national dialogue within Myanmar. However, there is a lack of clarity on the data on violence in Myanmar. In absence of any official record on data on violence in Myanmar in the last two years, an ASEAN perspective on this seems important and urgent.

(2) The ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management (AHA) Centre plays an instrumental role in providing humanitarian assistance to the citizens in Myanmar under the leadership of ASEAN. The statements mention about the partial delivery of aid to 400 IDP households in Hsiseng Township in Southern Shan State on July 7, 2023. The Joint Need Assessment (JNA) carried out by AHA Centre however has identified 1.1 million IDPs to whom they want to deliver aid. However, the statements do not mention about any timeline to reach out to these IDPs. They also do not provide any details about the challenges faced during the course of humanitarian action by the members of AHA Centre.

(3) The ASEAN Foreign Ministers meeting however mentioned the need for a comprehensive review of the 5PC implementation and the upcoming 43rd ASEAN Summit will examine the review report. They also continue their urge for multilateral cooperation involving the international organizations in addressing the challenges in Myanmar.

The February coup has halted the process of parliamentarian democracy and the nation-wide ceasefire. This commentary tried to look at ASEAN’s official position on Myanmar in the wake of the recent meetings hosted by ASEAN members. The simple fact that Myanmar is still a member of the ASEAN is sufficient to justify ASEAN’s stakes in the conflicts and turmoil in Myanmar. ASEAN’s 5PC is a diplomatic way to pacify the situation; it is not a real solution. ASEAN is also caught in the power game in Myanmar. During the time of President Thein Sein, China-Myanmar bonhomie was sidelined to the extent that Chinese funded Myitsone Dam project was halted. During the time of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, unexpected ‘pauk phaw’ (fraternity) developed between China and Myanmar. China continues to be a good ally of the Myanmar military too with strong defence partnership. Russia too supplies military equipment, weapons and fighter jets to Myanmar. These regional calculations are as complicated as the domestic situation inside Myanmar’s ethno-political scenario. Therefore, ASEAN makes cautious approach while dealing with Myanmar. Finally, ASEAN also has the mandate of non-interference to the internal affairs of one-another; ‘the right of every State to lead its national existence free from external interference, subversion or coercion’; and ‘Settlement of differences or disputes by peaceful means’. Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC) 1976 and other ASEAN foundational documents refer to these principles as the core mantra for ASEAN. Thus, ASEAN’s soft role in Myanmar’s crises needs to be understood and considered from the institutional and diplomatic point of view.

*CNF- Chin National Front, KNPP- Karenni National Progressive Party, KNU- Karen National Union, ABSDF- All Burma Students Democratic Front

[Photo by Gunawan Kartapranata, via Wikimedia Commons]

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

Dr. Sampa Kundu, Consultant, ASEAN-India Centre at RIS, New Delhi