With the seizure of British Paramountcy in the Indian subcontinent, princely states including the State of Jammu and Kashmir were asked to choose between India and Pakistan or remain independent. Till August 15, 1947, the day India became independent, this state failed to decide either way and increased pressure was natural from both the sides. It was in the last week of October that it had decided to accede to India keeping in view the security threats from Pakistan. After accession the Indian leaders and public as well faced the huge task of absorbing Muslim dominated Kashmir with India. It was a difficult task and demanded, for its accomplishment, virtues of statesmanship, generosity, farsightedness, accommodation and above all selflessness on their part. As a follow up of this motivation Article 370 of the Indian Constitution which conferred a special status on Kashmir was incorporated. Initially, soon after the accession in 1947, the Indian leaders made a good start and were generous in handling the Kashmir state affairs. The inserted article assured Kashmiris that they would be free to shape their own destiny as they desired and nothing would be imposed on them by the Indian Parliament. The Constitution makers were fully convinced that the close association of the people of Kashmir with democratic India would make them confident of their bright future by becoming an integral part of this Republic. In all these affairs Seikh Abdullah, the lone leader of the Kashmiri people, remained at the heart of the scene and formed an interim Government in Jammu and Kashmir.

Opportunistic Agreement of 1986

The State of Jammu and Kashmir witnessed its first reasonably democratic election in 1977 followed by a free and fair occasion in 1983. After the death of Sheikh Abdullah in 1982, his son Farooq Abdullah made an opportunistic agreement with Congress 1, the party ruling Delhi, in 1986 to remain in power. The accord that was arrived at between Rajiv Gandhi and Farooq Abdullah led to the formation of the National Conference-Congress coalition government in November 1986, it however, simultaneously alienated the large masses of Jammu and Kashmir. The argument implied that central aid would inflow as a result of the accord, was based on narrow considerations with no match to the self-respecting people of the state. In fact the party in power at the centre had no right to buy a share in the political power of a state by promising aid and the people of Jammu and Kashmir had repeatedly rebuffed attempts of earlier governments to take over their loyalty.

The accord was also full of other negative consequences. It was a denial of the basic principles of democracy and federalism. It implied that some states should be denied the right to be ruled by a government of their choice and it pushed once again Jammu and Kashmir outside the framework of federal democracy in India. It blocked all types of secular outlets of protest against governments both at the Centre and the State. It destroyed the raison d’etre of both parties and forced all types of discontent to seek fundamentalist or secessionist outlets. In no way the assembly elections of March 1987 was an improvement, blocking further secular and nationalist outlets of discontent, constitutional and democratic ones as well. Especially after 1987 all institutional channels of protest and dissent effectively blocked and even perfectly peaceful demonstrations were suppressed with lethal force.

In the circumstances the basic human urges that we witness in Jammu and Kashmir today were translated in insurgency/violence in the beginning of the nineties. The fact that Kashmir is now reacting to decades of Congress rule and by implication, of Centre’s political high-headedness is by and large accepted by most scholars. It is also to note here that because of the Pakistan factor, the insurgency in Kashmir has always had to be handled with greater firmness than those elsewhere. In most cases the problem is treated as merely an extension of the unresolved Hindu-Muslim conflict of the forties. There is no doubt that a large number of Kashmiri Muslims are alienated from India today. Their alienation is more as Kashmiri than as Muslim.

Expansion of insurgency in Kashmir

Factors responsible for the birth and proliferation of insurgency in the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir were many. Having permitted conditions within Kashmir to deteriorate to the level that they had reached in 1989, the Indian state had little option but to fight hard to break the insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir and the external support it was receiving. In fact, the democratic ideals of the freedom movement in India and its support to the struggle of the people of the princely states for a responsible government inspired and influenced the people in the valley. However, these very ideals remained elusive after the State acceded to the Indian Union. The alienation of the people of Kashmir made considerable headway due to the sequence of events that took place in coming decades. Kashmir policy of the Government of India has been marked mainly by what may be called the carrot and stick approach. But neither stick nor carrot helped win favour of the Kashmiri people. Force and aid were used as instruments to win the loyalty of the people not for the nation but for the Government and the Party in power.

Terrorism in Kashmir, or for that matter anywhere else, can not be ascribed to administrative or economic reasons alone. The main cause of it is the deprivation of political power due to which the community believes that its dignity and identity are threatened. In general secessionist-terrorist movements often seek outlets if the political system does not have adequate provision for its expression. This is what actually happened in Jammu and Kashmir after 1987. All institutional channels of protest and dissent which are essential to generating both democratic values among the citizenry and their allegiance to the established framework of authority were effectively blocked. Frustration and anger of the new generation accumulated and events began to take a new turn at the close of the Eighties.

Outside factors of terrorism

Expansion of insurgency in the State has an international aspect too. The Soviet intervention that took place in December 1979 and lasted about for a decade, had several far-reaching implications. It not only made available additional armaments to the insurgents but also changed the very nature of Pak society. Social disintegration appeared to escalate in the 1980s and 1990s. As both cultivation and drug smuggling escalated, Pakistan emerged as a frontline heroin production point and transit route for the international drug trade. According to a report about 5,000 Kashmiri youths were taken into Pakistan in the summer of 1988 for training and sent back in the spring of the following year. During 1988-94, over 50,000 Kashmiri youth are estimated to have been trained in Pakistan. Mujahideen, freed from the Afghan conflict, were sent to Kashmir and their numbers peaked at about 1600 in 1994.

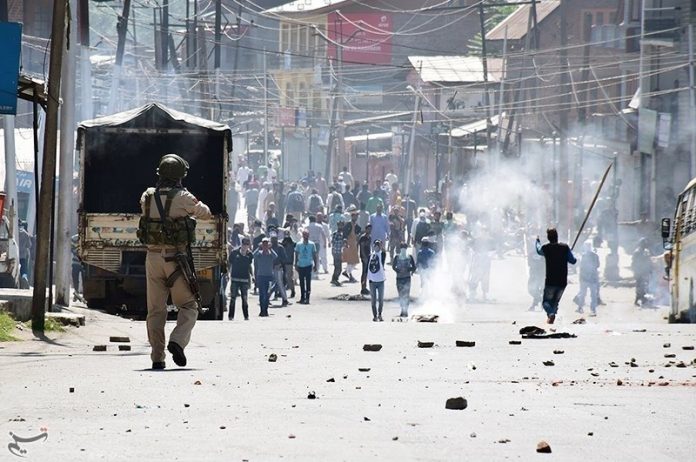

The struggle in the State of Jammu and Kashmir continued to evolve. The guerilla war rapidly intensified, to a significant degree because of an Indian response of repression and reprisal targeted not just against armed militants but frequently also against ‘disloyal’ civilian communities that aided and sheltered the rebels. Gradually, militancy entered a new phase. It was no longer a fight between the militants and the security forces. In fact it assumed the form of a total insurgency of the entire population and was marked by demoralisation within the political system, followed by the collapse of the administration.

Though the mid of the 1990s witnessed a wane to the local support for insurgency, in the second half of the decade Pan-Islamist fighters, primarily from Pakistan, infiltrated into Indian Jammu and Kashmir in significant numbers, adding a supra-local, strongly Islamist flavour to the conflict. The protracted ‘low-intensity’ warfare in the interior of the State between thousands of guerillas and hundreds of thousands of Indian security forces signaled a great transformation in the military and political character of the Kashmir conflict.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Geopolitics.

Dr. Rajkumar Singh is a University Professor for the last 20 years and presently Head of the Postgraduate Department of Political Science, B.N.Mandal University, West Campus, P.G. Centre, Saharsa (Bihar), India. In addition to 17 books published so far there are over 250 articles to his credit out of which above 100 are from 30 foreign countries. His recent published books include Transformation of modern Pak Society-Foundation, Militarisation, Islamisation and Terrorism (Germany, 2017), and New Surroundings of Pak Nuclear Bomb (Mauritius, 2018). He is an authority on Indian Politics and its relations with foreign countries.