Japan and Thailand have a storied history that dates back to the 16th Century, although most recall Japan’s invasion of Thailand in 1941 and the Kingdom’s subsequent declaration of war against the United States and Great Britain, which both the monarchy and the Thai Ambassador refused to deliver. The post-war era brought normalized relations between the two countries and Japan began to invest heavily in Thailand, where today it is home to numerous Japanese companies like Honda, Mitsubishi and Toyota, that provide a broad range of middle-class jobs. Over 1,700 Japanese firms employ roughly 1 million people across Thailand.

This past week, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced his resignation where in Japan has been met with mixed reactions, stemming from his handling of COVID-19 and a scandal plaguing both the Finance Ministry and his wife. In Thailand, Abe’s long tenure can be described as a mixture of pragmatism in his diplomacy after the 2014 coup d’etat and efforts to balance Japan’s relationship with Thailand, while not pushing it further into the clutches of Beijing.

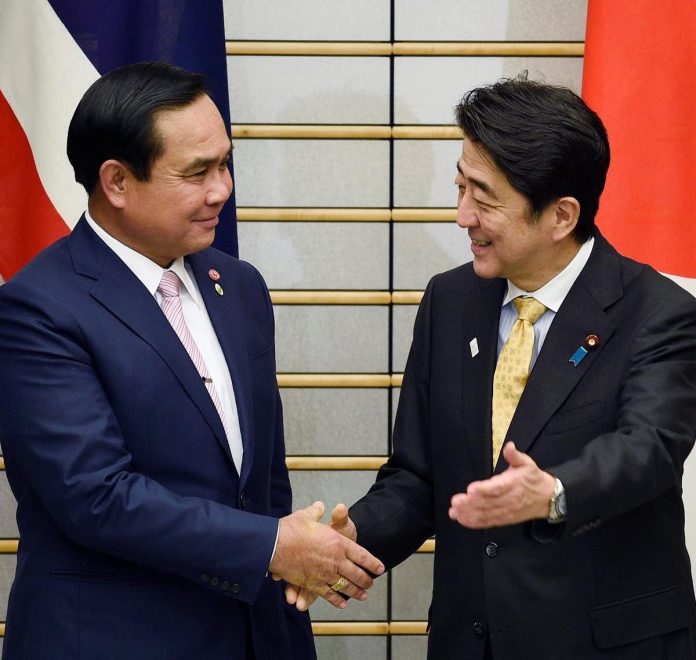

After the Thai military overthrew the government of Yingluck Shinawatra, Japan’s reaction was restrained, calling it “regrettable” and urged the return of democracy. Abe’s diplomacy afterward was balanced, advocating for democracy, while not wanting to lose any ground to China. Abe later met coup-leader and Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha in Tokyo in February of 2015, where he received assurances that elections would be held swiftly. Of course, that did not occur, as Prayut and the junta kept delaying polls until 2019, when conditions were set that made his election all but inevitable. Japan, however, wasn’t disappointed. It both expressed Abe’s reservations and protected Japan’s business and national interests in Thailand in broader Southeast Asia, a theme common in Abe’s tenure, evidenced by his dealings with Hun Sen in Cambodia.

The Chinese context in Japan-Thailand bilateral relations has always clouded the relationship. Both Japan and China have attempted to finance or make investments in high-speed rail in Thailand–China because of linkages to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Japan aiming to compete against rising Chinese influence. A proposed railway linking the northern city of Chiang Mai to Bangkok was ultimately scuttled over terms and Chinese infrastructure investments are already significant.

For Abe, Thailand has always been a tough nut to crack. While business ties have improved dramatically since the early 1970s when Thai nationalism and student activism saw boycotts of Japanese goods and Japan later countered with an attempt to have “heart to heart relations” with Southeast Asia. Risk-averse Japanese businesses have repeatedly complained about operating in an environment rife with political instability. Under Abe, however, Japan pragmatically found a balance between diplomacy, democratic values, and business, through initiatives across broader Southeast Asia like Thailand Plus One, which counters nervousness about increased labor costs and political volatility in China and the Japan-Mekong Cooperation, which recently has assisted countries in boosting health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Abe’s trade diplomacy also was consequential. After the United States withdrew from Trans-Pacific Partnership, Japan managed to salvage the deal minus the most powerful economy in the world, into what is now known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), of which Thailand is a part of. Abe’s pragmatism showed as Japan was willing to negotiate on sensitive issues like domestic agriculture. His departure also leaves the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement in some doubt because of the withdrawal of India in 2019. Abe’s personal relationship with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was considered critical in attempts to sway India to return.

Abe’s departure will likely not result in dramatic changes to the already strong Japan-Thai bilateral relationship. Japan remains Thailand’s third-largest trading partner behind the U.S and China. Abe’s LDP-chosen successor will likely not change Japan’s approach to Thailand, unless dramatic upheaval, either in the South China Sea or in Thailand’s domestic politics necessitates it. However navigating these two difficult challenges adeptly—both with its historic rival and Thailand’s choppy domestic politics—makes Abe’s performance in office far more than just adequate.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

Mark S. Cogan is an Associate Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at Kansai Gaidai University in Osaka, Japan. He is a former communications specialist with the United Nations in Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East.