Under President Donald Trump, American strategy toward the Indo-Pacific has been transactional. US allies such as Japan and South Korea have often been asked to pay more for supporting US troops. The two countries already pay a considerable amount for their defense, however, despite the ongoing costs, the Trump administration requirements were atypical in just how much money was asked for. Japan pays approximately $1.8 billion for US defense, yet the Trump administration asked for up to $8 billion. For South Korea, the costs amount to $900 million per year, yet the Trump administration demanded up to $5 billion during recent negotiations. The souring financial situation, combined with the fact that Trump often referred to the two US allies as “free-riders” makes it clear that America’s alliances in the Indo-Pacific are in a difficult position.

Japan has made major concessions to the US on trade, with little to gain, and the country has been trying to keep up with the changing geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific in a haphazard manner: it will scrap its Aegis-Ashore missile defense system, and is still working on developing an alternative solution to it. Aegis Ashore was abandoned due to a belief that it was not properly equipped to deal with the defense challenges Japan has to face. Trump’s diplomatic engagements with Kim Jong-un have changed little and offered North Korea time to develop its nuclear capacities. Under Trump’s watch, North Korea has refined its nuclear missile program to the point where it can hit the mainland United States. South Korea has tried to make the most of the tense diplomatic situation on the peninsula, however, the results have been mediocre. Trust in a Trump-Kim agreement decreased over time.

Trump’s China strategy has also exacerbated tensions in the Indo-Pacific. Given that the trade war between the US and China has mainly succeeded in hurting both and that under Trump’s watch China saw an opening to strengthen its hold on Hong Kong by eroding the little autonomy the city had left, a radical change of rhetoric came from the White House. By seemingly trying to emulate Cold War rhetoric, the Trump White House has framed its conflicts with China as a battle between a capitalist, free country and a communist one. It should be noted that previous US Republican administrations, such as that of George W. Bush, have chosen to sidestep China’s different style of government. The Obama administration was aware of changes in China’s ambitions, yet it also refrained from fueling Cold War rhetoric.

As a response to China’s assertiveness, the US eventually decided to support the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, also known as “the Quad”, a strategic platform that unites the US, Japan, Australia, and India. Japan has generally supported the Quad, while Australia has also engaged with the security platform as a useful forum. Due to tensions with China at its border, India has also moved away from its decades-long strategy of finding the strategic middle ground and became more interested in working within the Quad. While the Quad has become more coherent, some US allies like South Korea do not see it as something that can enhance their own geopolitical ambitions.

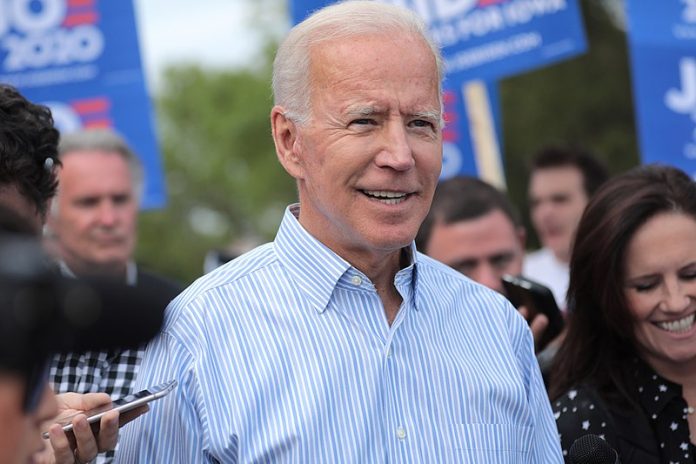

How would a Biden administration deal with America’s allies in the Indo-Pacific?

Trump was transactional with America’s allies, he did not shy away from conflict and especially publicly berating his allies, and the US was more than willing to describe China as an enemy during the Trump years. A Biden administration will mark a return to a more multilateralist foreign policy. Biden has outlined his foreign policy vision before the 2020 primaries began. It consists of two major pillars: firstly, America must reconnect with its allies and secondly, it needs to retake its seat at the head of the table.

A readout of Biden’s calls with the Prime Ministers of Japan and Australia, as well as South Korea’s President points out the following: America seems interested in increasing cooperation and refraining from criticizing its allies, at least in the open. The US has reasserted its promise to defend Japan without mentioning any economic requirements for upholding Article V of their defense treaty. Biden still seems to see South Korea as part of a regional foreign policy debacle: tensions on the Korean peninsula. It is possible that climate change will provide an opening for South Korea to move outside its “traditional” category for Washington strategists, and be viewed by the US as a regional power with a heavy say on other world affairs too. Climate change has emerged as a common denominator for all four countries, and that can help establish a new area of multilateral cooperation.

Biden will have an uphill battle in convincing US allies that America can lead again. Japanese conservatives remain skeptical of a Biden administration due to fears that it would soften its stance on China. Biden has tried to counter that by re-affirming that the US-Japan Security Treaty also applies to the disputed Senkaku Islands, a security battleground between Japan and China. By doing this, Biden is signaling a return to the landmark Obama statement which confirmed that the US perceives the Senkakus as part of Japan. South Korea’s current Moon Jae-in administration will certainly be more optimistic about Biden than Japan’s Suga Yoshihide, both Presidents are liberals. However, South Korea no longer wants to be regarded as an afterthought in the US, and Biden has hinted the he’s willing to listen more to South Korea when engaging with North Korea, however, how deeply will he adhere to that remains to be seen. As for Australia, the relationship’s upcoming ups and downs mirror those of America’s East Asia allies: Prime Minister Scott Morrison has been very receptive to the US tough line on China, however, Biden’s interest in climate change might put Canberra in a difficult spot. As for the Quad, the Biden transition team has not spoken too openly about it. The current impression is that cooperative talks will continue, however, ambitions that the Quad will become a NATO-like structure need to put on pause. The Quad is still an unfinished structure, and while many see it as a military structure, some have hinted it could become a platform for economic cooperation.

Another way the US could economically restart its relationship with its allies would be by rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Biden has hinted a willingness to rejoin the TPP, however, Democratic party’s more protectionist stance would make rejoining the agreement difficult. Another area where Biden could improve is the World Trade Organization, another structure that was often criticized by Trump. The WTO will elect a new head soon, and the US supported former South Korean Trade Minister Yoo Myung-hee, a move that Japan has not welcomed. The competition for the next WTO head is becoming increasingly tense, as the European Union leaned toward supporting Yoo’s rival candidate, Nigeria’s Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala.

To conclude, there is clearly a willingness from Joe Biden to bring America’s allies to the table and try to work out solutions, preferably with the US leading. However, it will be up to Biden’s foreign policy team to navigate tensions between America’s allies and China or Iran, but also between America’s allies themselves. Biden will try to create the impression of a return to normal, but pre-2016 normality is no longer feasible. US allies have lost considerable trust in the US during the Trump years and mending those ties will require time. America must try to improve relationships wherever it can, and most importantly, lead by example, preferably by attempting to fix its own domestic problems, in order to restore credibility and trust with its allies.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

The author is an international relations PhD student at UCL on hegemony, burden sharing and alliance free-riding. He has received his M.A. from UCL and B.A. from Queen Mary, University of London.