While building on the theme of uncertainty in his book ‘The Black Swan’, Nassim Nicholas Taleb talks about the writing of history and how there have been times when trained historians could not foretell events which would be starkly evident in hindsight.

As an example, he describes William Shirer’s book ‘Berlin Diary: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent, 1934–1941’ and concludes; ‘one would suppose that people living through the beginning of WW II had an inkling that something momentous was taking place. Not at all.’ He further adds: ‘some comments here and there were quite illuminating, particularly those concerning the French belief that Hitler was a transitory phenomenon, that explained their lack of preparation and subsequent rapid capitulation. At no time was the extent of the ultimate devastation deemed possible’.

It is possible that post-WW II commentators were conscious of the above and erred on the worst case during the numerous flashpoints of the Cold war – a World War III was said to be imminent — during the Korean war in the 1950s, the Cuban Missile crisis in the 1960s, the Arab-Israeli war in 1973 and the USSR’s Afghanistan invasion towards the end of the ’70s’. Thankfully better sense and the nuclear overhang prevented wider conflagrations – debatable but a part of the consensus and not the intent of this discussion.

Since the 1990s and especially during the 2010s China has replaced the USSR as the US’s sparring partner and several geographical (apart from ideological) friction points have emerged. These are currently restricted to the periphery of Chinese land and sea borders; and while not impacting the US directly, threaten its alliance and treaty partners in the region.

Even before Trump’s Trade war and the Covid-19 Pandemic, the question(s) being asked across all forums were this:

- What is the probability of the current frosty relationship becoming a full-blown ‘Cold War 2.0’?

- What are the ‘Red Lines’ which when crossed, will turn non-kinetic confrontations into ‘hot conflict’ and what would be the consequences – for Asia and the wider world?

Lines in the Sea

In 2007, just then transferred to Kuala Lumpur, I remember a lunchtime conversation with a colleague who had laid out the irony of the ongoing South China Sea dispute wherein the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia have overlapping/intersecting claims in the South China Sea. China on the other hand not only overrules the claims by these countries but also asserts its sovereignty over “virtually all of the South China Sea islands and their adjacent waters” based on its ‘historical’ but largely unsubstantiated claims. To do this China makes use of a ‘Nine Dash Line’ that ‘swoops down past Vietnam and the Philippines, and towards Indonesia, encompassing virtually all of the South China Sea’, to delineate its claims.

If the SCS flashpoint for Philippines-China is the Scarborough shoal in the West Philippines sea; for Malaysia, the flashpoint has become the Luconia shoal. It was in June 2015 that Malaysia discovered a Chinese Coast Guard vessel ‘anchored’ in a semi-permanent deployment at these shoals (called Beting Patinggi Ali by Malaysia).

Malaysia hitherto having chosen to take a low-key approach to the South China Sea demarcation disputes — as compared to the Philippines or Vietnam — was finally forced to react. Malaysian Navy and Coast Guard vessels were deployed near the Chinese vessel to observe and Shahida Kassim, a minister in the Malaysian Prime Minister’s Department even took to discussing the incident on Facebook. An ‘official protest’ was also lodged with Beijing.

The protest notwithstanding China has chosen to continue with its aggressive tactics and Malaysia has come under increasing and unrelenting pressure on its Borneo maritime boundary since 2015. In July 2020, the Malaysian government put out an official report (National Audit Department) stating that Chinese Coastguard and Naval vessels had intruded into Malaysian waters a total of 89 times between 2016 and 2019. Even when confronted by the Malaysian Navy the vessels remained in the area. The same report mentioned that Malaysia has lodged six diplomatic protests over continuing encroachment in its territorial waters.

Chinese Coast Guard Vessel 5402

The dispute does not seem to be heading towards a resolution any time soon and will get a lot worse before it gets better (hopefully). To illustrate this point – two other recent incidents need to be underscored – the first was the November 2020 harassment of an Oil rig deployed in Malaysian waters by a Chinese Coastguard vessel and its subsequent stand-off with the Royal Malaysian Navy’s KD Keris (a littoral mission ship ironically built by a Chinese shipyard).

The incident would have gone unreported had it not been for the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI), — an initiative for analysis and data sharing by the Centre for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) a Washington, DC-based think-tank. Analyzing satellite and maritime traffic data provided by a company called Planet Labs and reviewing vessel paths, the Institute was able to deduce that the Chinese Coast Guard vessel 5402 started off from Hainan Island in October 2020 before making stops at the Chinese Spratly Island bases of Subi and Fiery Cross (‘artificial Islands’ and therein lies another tale). It finally positioned itself for a ‘tour of duty’ at the Luconia shoal and in Nov 2020 decided to investigate the Borr Drilling Jack-up ‘Gunnlod’ that was prospecting close to the Luconia shoals. It not only approached the drilling rig in a threatening posture but also interfered with its support vessels as they made their runs to the rig and back. The rig was only 82 kilometers from Malaysian Sarawak.

People’s Liberation Army Air Force Acts

The second incident has been much more recent – much more widely reported by international news outlets compared to the first. Note: as an Indian observer I still get surprised by how sanguinely these events are covered by the already sedate Malaysian media (when compared to their raucous Indian counterparts). Besides the media, one can sense at a governmental level there is a realistic and mature acceptance of the balance of power. China is Malaysia’s largest trading partner, and while the former PM Mahathir Mohammad early on in 2018 had canceled some of his predecessors’ Malaysian ‘Belt and Road’ projects with China; the economic engagement continued. Finally, and however minimal, there might also be a consideration of the potential impact on internal relations – remember Malaysia has a sizeable Chinese diaspora — and while it has done a remarkable job of melding a Malaysian identity; its political economy has undergone a chaotic decade with emerging internal fractures which would be best repaired than exacerbated. It needs to be recalled that in 2015 the Chinese envoy Huang Huikang had been pulled up for interfering in Malaysian affairs by making a remark on ‘discrimination against races’.

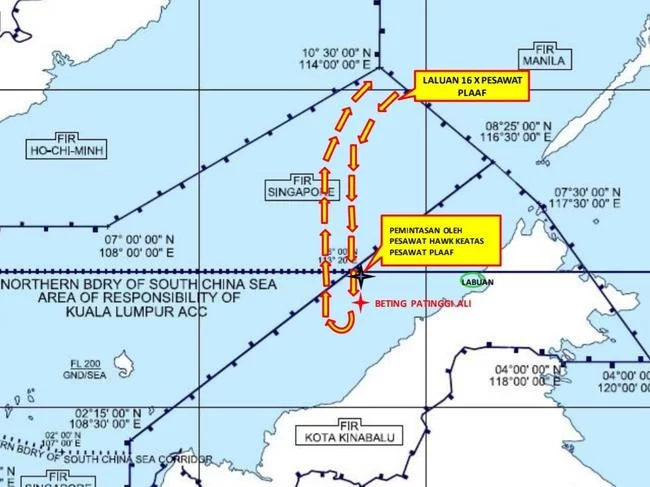

As to what happened — on May 31, 2021, the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) reported that its fighter jets had scrambled when 16 Chinese military aircraft approached Malaysia’s coastline in Sarawak, located on the island of Borneo. The Chinese air armada, comprising a mix of its largest transport aircraft the Y-20 and the Russian IL-76 – nicknamed ‘Gajraj’ in the IAF, crossed into Malaysia’s Maritime Zone (MMZ). The incident was almost a repeat of what the PLAAF (Peoples Liberation Army Air Force) is doing on a regular basis in Taiwan. Analyst Collin Kho from Singapore’s S Rajaratnam School of International Studies tweeted that “such a move is not only a blatant intimidation against Malaysia, but also predatory and opportunistic”.

RMAF issued a detailed statement on 1st June 2021 where it outlined that its fighters were scrambled from the Labuan airbase and concluded by saying that “The PLAAF formation, followed by the Malaysian fighters, continued on past the Luconia Breakers, coming as close to as 60 nautical miles off the Sarawak coastline before turning back”.

Malaysia and the limits of ‘quiet diplomacy’

Since the incident, Malaysia’s response has been measured but in the same vein as earlier: the Chinese ambassador in Kuala Lumpur was summoned for an official explanation and to relay Malaysia’s displeasure at the incident. “Malaysia’s stand is clear – having friendly diplomatic relations with any country does not mean that we will compromise our national security. Malaysia remains steadfast in defending our dignity and our sovereignty,” Malaysian Foreign Minister Hishammuddin Hussein stated in the statement. The Chinese reaction was also in character – with its embassy stating that the aircraft were on routine training and did not target any country or enter territorial airspace.

What is coming up next? And how far will the Chinese ‘ratcheting up’ of the dispute with Malaysia go? Remember that Malaysia is an integral part of ASEAN which has been working towards a formalized ‘Code of Conduct’ (CoC) with China to control disputes and improve cooperation. This CoC intends to build upon the 2002 non-binding Declaration of Conduct (DOC) signed between China and ASEAN – with the aim of promoting peace and stability in the region. However, ASEAN itself has several non-claimant members and has enough internal divisions – which means Malaysia cannot depend on it alone to resolve bilateral issues.

From a security perspective, Malaysia is an informal part of the American security architecture in the region. It even has a formal treaty under the Five Power Defense Arrangements (FPDA) with the UK, Australia, Singapore and New Zealand – the fact that no one seems to mention this treaty, indicates a level of redundancy in its 50th year (the treaty was signed in 1971).

What other options does Malaysia have? Besides strengthening its own security infrastructure and greater engagement with the American security umbrella, does it need to start formalizing security alliances and pick a side? ‘Quiet diplomacy’ – Malaysia’s preferred method of addressing bilateral issues with China, without publicizing matters – clearly does not seem to have improved the situation. This ‘Quiet diplomacy’ has been termed ‘playing it safe’ in a 2016 article by Prasanth Parmeswaran, a regional security expert, when he says that the approach might have reached its limits and a recalibration was in progress.

QUAD and ASEAN – evolving relationships

Looking at the latest developments in the security situation in the Indo-Pacific; would the Quadrilateral Security dialogue, which has regained traction after more than a decade in limbo, be a formal security option for Malaysia? The Quad itself is in a phase of defining its terms of association – and has a long way to becoming a formalized security alliance in the manner of an ‘Asian NATO’ if it at all evolves in that direction. The latest trend of increasing tensions between China and individual Quad countries – India, Australia and Japan – might hasten formalization, but it is still not a given.

Remember ASEAN itself has a certain internal ambivalence on how it needs to engage with the Quad – since it would represent a shift away from the fundamental tenet of ‘ASEAN centrality in the region. For its part, ASEAN might prefer to use existing institutional mechanisms created and led by it – primarily the East Asia Summit (EAS) or the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).

Prima facie it can be assumed that constituents like Malaysia might prefer not to engage formally with the Quad given their ASEAN commitments. Even if threat perceptions rise to levels that they do make unilateral decisions – the decision will not be taken lightly since it will be at the cost of infuriating a powerful China which has stated that the Quad is confrontational and an attempt to ‘contain’ its ‘peaceful rise’.

There are no easy answers and it is likely that in short-term Malaysia will continue to walk a tight rope. In my opinion, we seem to be careening slowly, just as in the 1930s, to a point where the price of ‘quiet diplomacy’ and non-confrontation could only embolden an aggressive and revisionist hegemon. Hopefully, history will not repeat itself.

[Photo by Voice of America, Public Domain]

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

The author is a senior oil & gas executive with over 25 years in the industry. He has held various assignments in Asia, the Middle East and Africa.