The Reang/Bru/ ‘Tuikuk’ (a term used by the Mizo to refer to the Reang/Bru) is primarily restricted to Mamit and Kolasib districts in the northeast Indian state of Mizoram. Like the Chakma, the Reang/Bru/Tuikuk are branded ‘Problem tribes/people’ by the Zo hnahthlak. Popular social imagery of the Reang/Bru/Tuikuk among the Zo people is that of a ‘non-human’, a primitive entity.

The Reang or Bru as they call themselves have been strongly resisting the subtle process that has been initiated by the northern majority tribes — the ‘Mizo’. The stoic resistance of the Reang/Bru people towards the initiatives of the Zo hnahthlak to proselytise and tame the backward people has ended in unfruitful results or results contrary to the expectations of the northerners. Thus, the Reang/Bru people are scorned by the Zo hnahthlak as ‘Tuikuk Pathian siam theilo’ ‘kha siam kan tum’ (‘we are trying to make humans out of those people who failed God’). The large number of missionaries being sent to the Reang areas to bring them to the fold of the book (Bible and the Law) reflects the mission of assimilation within the Mizo Identity. The state is sponsoring studies to come out with reliable work to support their Zo/Mizo linkages to tone down the emergent ethnic consciousness built around the ‘Koch-borok folklores’ of the Koch and Bodo tribes of Assam and Coochbehar.

The origin of Reang is believed to be Maian Tlang, a hill near Rangamati in Bangladesh. Few studies suggest a wave of 14th-century migrations from the Shan state of Burma to Chittagong and then into Tripura. The Reang folklore of the two brothers Bruha and Braiha speaks of the west-ward migration of the Reang. The party led by Braiha in the course of the migration went ahead, and the party led by Bruha failed to catch up with the elder brother. As a result, the party led by Bruha stayed back in the Zo hills and came to be known as Bru. In contrast, the party led by Braiha went ahead into the Chittagong Hill Tracts and from there on to the present day Tripura. It became the original settlers of that region.

Pem Chuak (Move out): The flight to Tripura

The ethnic clashes between Mizos and Brus through the mid-1990s resulted in the demand to remove the Reang/Bru people from the state’s electoral rolls by the vigilante groups- the Young Mizo Association (YMA) and Mizo Zirlai Pawl (MZP). The state government in 1995 succumbed to the pressure tactics of the vigilante groups. It declared the Brus/Reangs ‘not indigenous’ to Mizoram. This was followed by over two decades of ethnic unrest led by the militant outfit Bru National Liberation Front (BNLF), and a political outfit the Bru National Union (BNU). These movements sought political autonomy and demanded a Bru Autonomous District Council.

The ousting and dispersal of the Reang/Bru people adversely affected the geopolitics of the region. The neighbouring Indian state of Tripura became the first point of transit and shelter for those fleeing the ethnic rumblings in Mizoram. The displaced Reang/Bru took refuge in a town called Kanchanpur in northern Tripura, on the Mizoram-Tripura border. Spread across seven refugee camps on the Jamui hills that separate Tripura from Mizoram and Bangladesh. The number of Bru refugees living in these camps is disputed. Some reports claim around 35,000, while others provide a higher estimate.

The Reang/Bru living in the camp alleged that the Tripura government and local tribes from Tripura were making life as difficult as possible for them to leave. Residents of these camps are not entitled to employment opportunities under any government scheme. The reports from the camps in Tripura also mention the meagre allowances and lack of access to potable water and medical services.

The repatriation talks with Mizoram and stakeholders were stuck repeatedly by stray incidents of violence and waves of flights to Tripura. For instance, in November 2009, Bru militants reportedly killed a Mizo teenager, triggering another spate of brutal retaliatory attacks on the Brus who had stayed behind in Mizoram, and another round of exodus to Tripura.

Fisted ethnic stands

The back-migration of the Reang from Tripura to Mizoram has made the various bodies of the Reang/Bru apprehensive of Reang/Bru returnees’ safety in Mizo-dominated villages. They demanded cluster villages for the Reang/Bru. The Mizoram government has termed the demand ‘unreasonable’.

The Bru/Reang are Jhumming communities. Much of their apprehensions of re-moving (Pem Lut) to Mizoram arise from land concerns, land entitlements. The demand for five hectares of land per family was objected by the state government and the Zo vigilante groups. The Reang/Bru ‘demand list’ to the Mizoram government includes one government job per family, cash assistance of Rs 1.5 lakhs for each repatriated family and others. The Reang/Bru allege that the Mizoram government has not identified around 1,000 families living in camps in Tripura as ‘eligible to return’ to Mizoram.

The Reang/Bru cited community hurt on this selective stand of the Zo hnahthlak on the issue of a right to return to the homeland. The Reang/Bru criticised the Zo Civil Society and the Churches for restricting the path to ‘Pem lut.’ The state government of Mizoram and the vigilante stakeholders like the MZP, YMA have accused the Reang/Bru leadership of deliberately sabotaging the repatriation process by repeatedly changing their demands.

The dilatory tactics adopted by the Mizoram government and its consistent refusal to consider either of the demands even after ten rounds of peace talks have induced rethinking in the BNLF ranks.

Ethnoreligious Moodswings

The issue of Reang/Bru ‘coming Home’ has startled the Zo hnahthlak in Mizoram. Public debates and the sermons from the Pulpit across the state have questioned the issue of the Reang/Bru’s right to return (Pem Lut (Move-in)). Communitarian actions and political interventions are interpreted through the ecclesiastical lens. The civil societies and vigilante groups in Mizoram suspect the Reang/Bru ‘coming Home’, the return of the ousted problem people is seen as a move to destabilise the Ideal Zo Christian State.

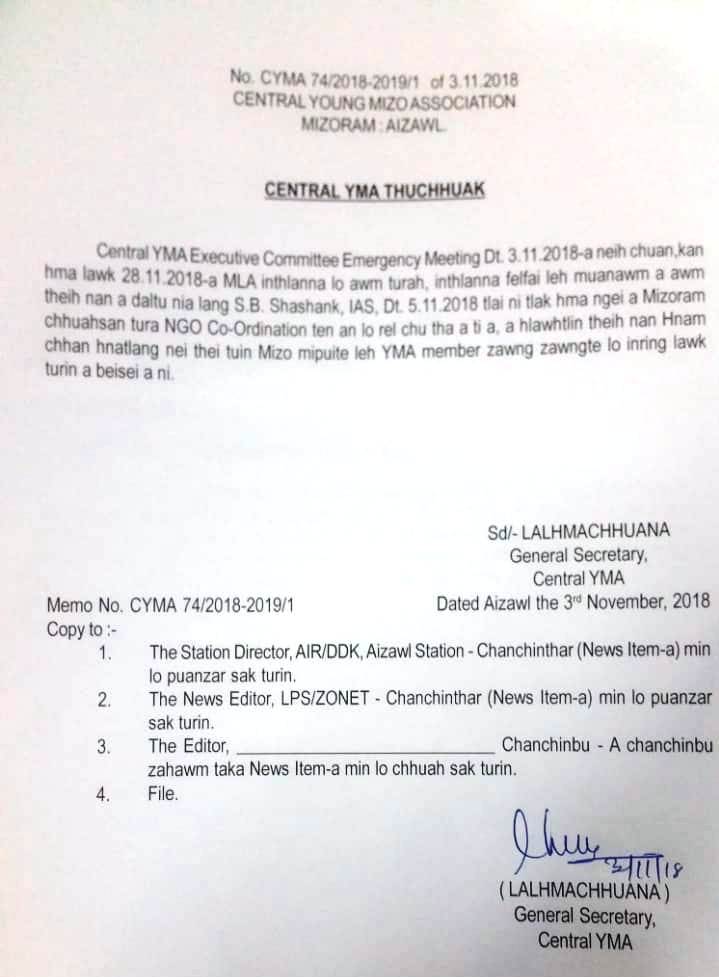

The electoral dispute that engulfed Mizoram throughout November 2018 needs to be gleaned against a larger backdrop of fisted ethnoreligious mood swings. Protest rallies demanding the ouster of the State’s Chief Electoral Officer S.B. Shashank for allegedly misusing his official position to transfer a Mizo IAS officer. In his report, Shashank had held the Mizo IAS officer to be ‘responsible for restricting the return of the Bru/Reang and being a sympathiser of the Zo hnahthlak.’ According to Shashank’s report to the ECI, the action against the Mizo IAS officer Mr. Chuaungo had its genesis in the “unprecedented” theft and destruction of 5,400 electoral roll revision forms August 23-24 from Mamit. Apart from interfering with the revision of the electoral rolls in Mamit, Mr. Chuaungo meddled in the “process of security management of conduct of election.”

The protest rallies across the state attempted to halt the entire election process and the elections scheduled in December 2018. The protest movement took the form of a viral wave in the form of ‘Save Mizoram Movement’ both in real and the virtual space. Banners and posters displayed by the protesters asked the Election Commission of India to call on S. B. Shashank. “You will be responsible if Mizoram’s record of holding the most peaceful elections in India is turned into a nightmare,” one of such posters read.

The vigilante groups of the Zo hnahthlak craftily converted the issue of a transfer of a junior incumbent by a higher incumbent as an ‘insider versus outsider’ issue. The social media and medium of Whatsaap were used to replay the tensions between ‘sons of soil’ vis a vis ‘outsiders’, and the need to be fisted and protect Mizo/Zo culture and identity from polluting infiltrators through the hashtag movement #shashankout #supportchuaungo.

On 2 November 2018, S. B. Shashank was issued ‘Quit Mizoram Notice’ and asked to leave Mizoram by 5 November 2018 for having Lalnunmawia Chuaungo (1987-batch Mizo IAS, Gujarat cadre) transferred out for interfering with electoral rolls of the displaced minority Bru community.

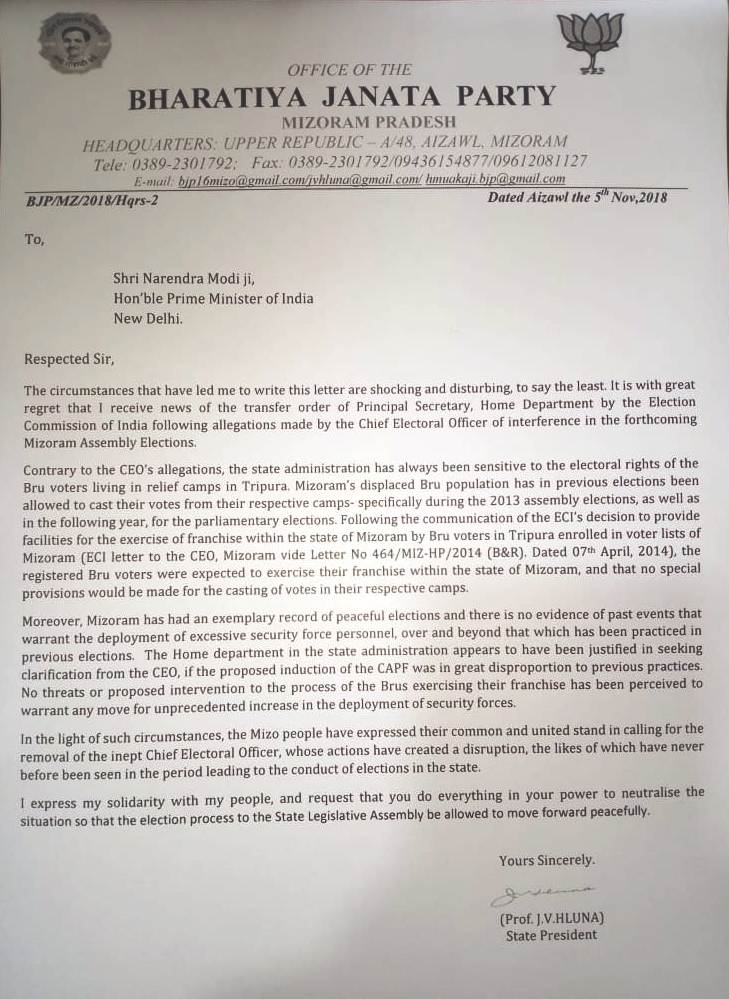

The regional political parties rallied behind the Church and the vigilante groups as they found it safe to go by the Church-based bodies’ diktats. The Mizoram Pradesh Congress accused Mr. Shashank of being a Bharatiya Janata Party stooge and sought his removal. The BJP, trying to gain a foothold in Mizoram, also demanded Mr. Shashank’s ouster in a bid to trash the allegation of the Congress.

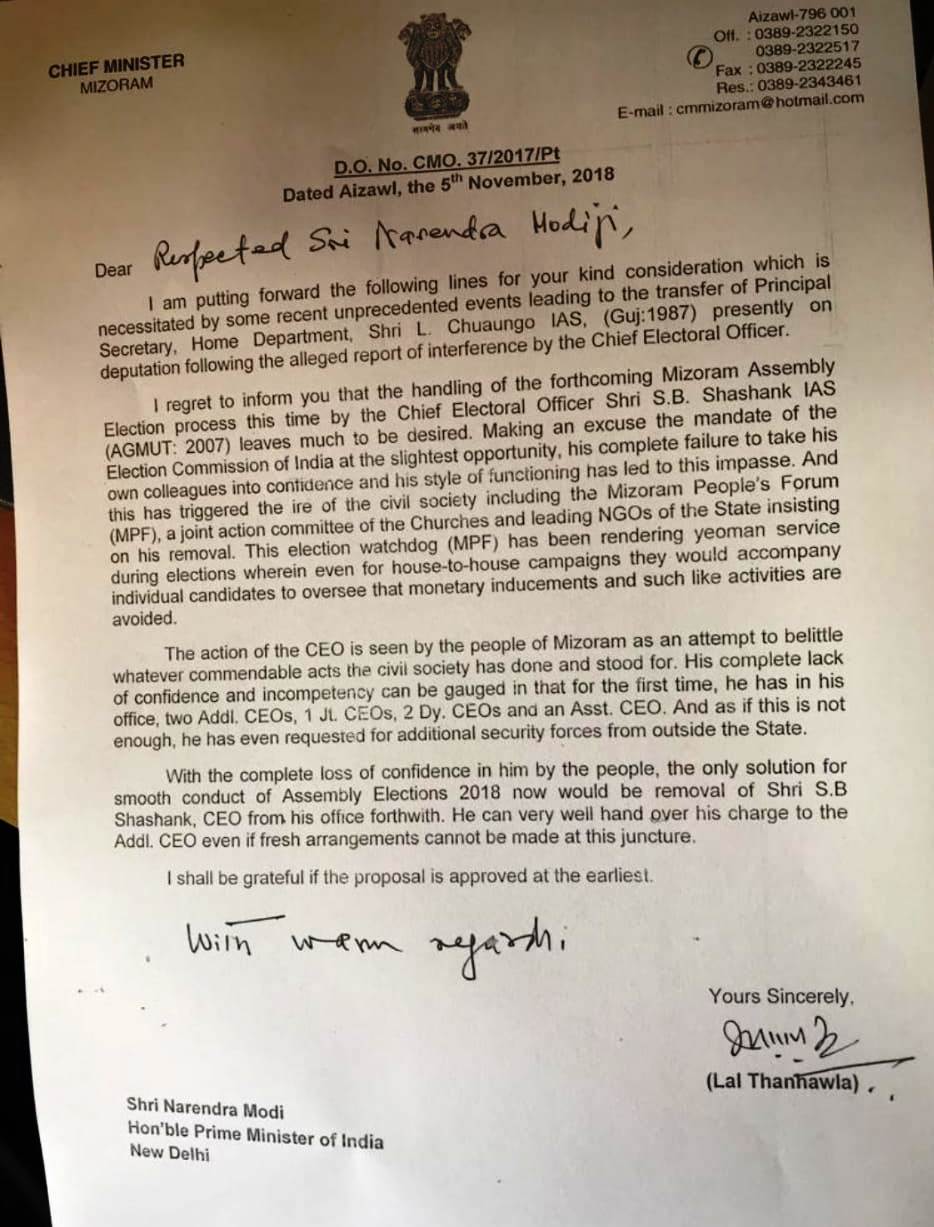

In a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Chief Election Commissioner on 3 November 2018, the then Chief Minister Lal Thanhawla (Congress) sought Mr. Chuaungo’s reinstatement -the Principal Home Secretary. The ECI had, following Mr. Shashank’s complaint on 29 October placed Mr. Chuaungo under the disposal of the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). The Letter of Congress described Mr. Shashank “inexperienced and incompetent”. It said the civil society in Mizoram “does not take this (inept handling of electoral process) lightly” and that the government fully supports “their long-standing demand that the Brus now living in Tripura transit camps should come and cast their votes inside Mizoram like every other Mizo from outside the State do at the time of elections”. The fisted ethnic rumblings were toned down with the removal of Shashank.

The Reang/Bru from the late 1990s have been mooting their religio-cultural differences from predominantly Christian Zo hnahthlak. Their experience of being ousted overnight into the borders of Tripura substantiates their collective fears and insecurities of living among the Zo hnahthlak. The collective fear was used to permit the Reang/Bru to vote either from refugee camps in Tripura and Assam or poll booths on the Tripura-Mizoram border. The Zo hnahthlak from Mizoram, in turn, suspected this as a ploy to increase the ‘Tuikuk (Reang/Bru) vote banks’ and affect the demography of the state election.

The Reang/Bru case shows differences and commonalities in issues relating to minorities within minorities in the state of Mizoram. The Reang/Bru are selectively marked as destabilisers of peace in the Ideal Zo Christian State and the source of conflict in peace-loving Mizoram. The ethnic rumblings spillover to the virtual spaces and complicate the contentious relations between tribal communities further in the form of hashtag movements and circulation of contagious messages in viral videos, memes etc. The majoritarian Zo hnahthlak identifies the non-believers like the Reang/Bru and the Chakma as ‘trouble makers’. This conjures stereotyped social imageries of Reang/Bru as spoilers of peace, ‘markers of backwardness’ to be tucked away from Mizoram. The contentious ethnoreligious claims and claims-making charted in this discussion broad-brush the vexed issues of ethnic rumblings and political moodswings that loom more extensive in the geopolitics of India’s northeastern borderlands.

The author is an Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science & Political Studies, Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, Kolkata; and member Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (MCRG), Kolkata. Also Visiting Faculty, Department of South and South East Asian Studies (SSEAS), University of Calcutta.