Renewable energy plays a vital role in achieving energy security – a pressing issue for developing countries such as India. Alliances such as BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) can prove to be extremely advantageous if they invest in clean energy and leverage their combined potential to push for more stringent, legally binding protocol at a national and international scale. In the past decade, investment in renewable energy by the BRICS block increased by almost threefold. More recently, however, the pace of development in this sector has taken a hit. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the energy sector has also shown the need for stronger policy framework and the exchange of local solutions and technologies.

India in the bigger picture

Despite the progress made in the last decade, as of late 2019, the Indian renewable energy sector’s growth had fallen to a five-year low. The COVID-19 pandemic might add further strain to the sector. For example, one of the short-term impacts in 2020 could be the loss of 2-3 gigawatt (GW) capacity addition. This is significant considering that the country has set an ambitious goal of generating 175 GW of renewable energy by 2022. Research also shows that the medium-term consequences of the pandemic could range from policy uncertainty risks to a push for local manufacturing.

Therefore, now more than ever is the time to push funding for comprehensive energy research, development, and deployment (RD&D) which plays a critical role in shaping India’s energy policy goals. And collaborating with international partners that have similar needs could prove to be valuable in the long run. International multilateral agreements often boost ambitious and stringent national policies. They also serve as much needed incentives for the private sector to commercialize renewable energy technologies. Additionally, such collaboration could serve as a means of strengthening diplomatic ties using environment, energy, and climate change as the backdrop. It could also offer India significant clout and increased negotiating power at global summits such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) where the country is already a part of blocks such as BRICS, BASIC, G4, G77, etc.

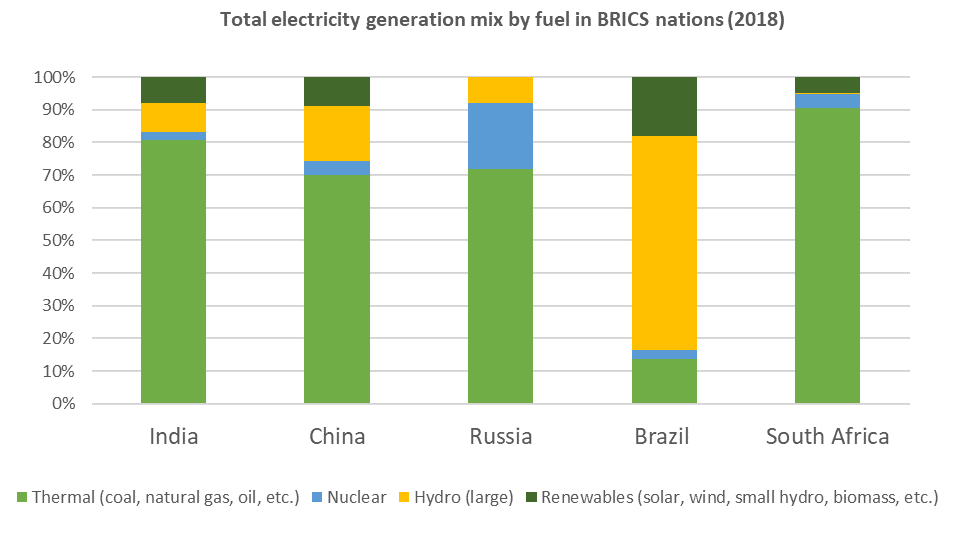

Some international conferences have been criticised in the past for failing to achieve any significant large-scale impact due to the lack of consequences that countries face when targets are not met. Besides, some decisions are usually opposed by developing economies which see them as a threat to their development. For example, some of the biggest opponents of carbon emission cuts proposed at the UNFCCC 2019 included India, China, Russia and Brazil. However, as countries where renewable energy already takes up a significant portion of the total electricity generation, and there is scope for far more, these nations are truly poised to take the lead in this matter. The shift to clean energy does not have to come at the cost of development; rather, it should be perceived as a key factor in boosting development and economic growth and empowering these nations in the long run.

BRICS: An influential stakeholder

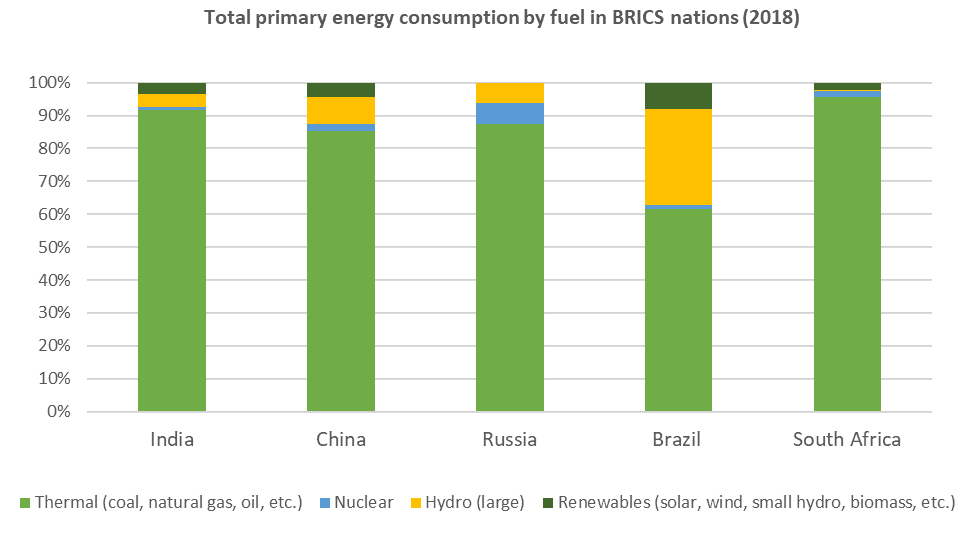

BRICS constitutes approximately one-third of the world’s population as well as one-third of the world’s GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. BRICS countries also account for 36 percent of the global primary energy supply and this share may surge by almost 50 percent by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). This allows the block to wield tremendous influence over the future of the global clean energy transition as they play a crucial role in the world economy and energy market. This transition also favors the individual nations as it lowers the costs of renewables, boosts ‘green collar’ employment and leads to enhanced energy security and local air quality.

Despite engaging in talks surrounding the energy sector since 2009 and setting up mechanisms such as the New Development Bank of BRICS (NDB), most of the energy cooperation between BRICS countries remains at a bilateral level. For example, the joint Indo-Russian project to build the Kudankulam plant in Tamil Nadu, the largest nuclear power station in India. Various factors have obstructed BRICS multilateral energy cooperation – from inter-group competition to different socio-economic approaches to development. There is also the continual threat of dwindling interest in cooperation as all BRICS nations already have established ties with other countries outside BRICS, whom they depend on for their energy supply.

In line with India’s declining trend, investment in renewables has decreased in other BRICS nations too – partly due to falling costs. China – the second-largest producer of renewable energy in the world – has been facing a slowdown in the clean energy transition due to lower government investment. Brazil, a country where 75% of the new electric power comes from water-generated energy, has been slow to enter the solar and wind power landscape. South Africa and Russia, which have huge potential to develop solar and hydroelectric energy respectively, have not yet made these sources a significant part of their energy mix.

However, the potential that BRICS possesses is still massive. It can be a strategic step geopolitically as well – by increasing the share of renewables in the required energy mix, countries can alleviate geopolitical tensions and reduce dependence on unstable regions for their energy supply. As opposed to clean energy, nations dependent on fossil fuels, heavily rely on fossil fuel-rich countries which creates a necessity for extended military protection in order to secure transportation routes.

Global frameworks, local solutions

With smarter planning, developing economies can also come up with indigenous solutions. For example, Brazil is known for its usage of sugarcane alcohol, which it uses to power more than half of the country’s car fleet. In India, voluntary initiatives such as the Barefoot College in Rajasthan, which teaches rural women and men to manufacture and install solar panels, have been successful as well. The Barefoot approach has already found success in other countries in Asia, Africa, and South America as well. Such cases exemplify how making use of locally abundant products and using decentralized approaches can enable developing countries to gradually shift to green energy in an innovative yet efficient manner.

In the Altai Republic of Russia, nomadic communities make use of portable solar panels which allow them to migrate comfortably while continuing to engage with their traditional livelihood. Such indigenous communities are also present in other BRICS nations such as India and Brazil, where their territories are strongly associated with solar, geothermal, and other resources. BRICS could thus collaborate on how to better engage with such communities to find culturally appropriate energy solutions. ‘Glocalization’ – adapting global ideas to local contexts – could therefore be a possible answer because while the challenges might be global, the on-ground solutions need to be local.

Further, energy security is inherently linked to environmental problems such as climate change. These problems transcend national borders and developing countries tend to experience some of the worse repercussions. They also potentially hinder international cooperation, which is why researchers believe there is a growing need for global environmental governance. It might, therefore, be in the interests of these nations to share their knowledge, technology, and resources with each other for a better sustainable energy transition instead of looking to the global North to lead the way. Paired with trade facilitation, complementary energy strategies may prove beneficial to every member of the group.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

The author is an intern at Conservation Action Trust. She has previously completed internships at India Development Review, Mumbai and Seva Mandir, Udaipur. She holds a BA in psychology and anthropology from St Xavier’s College, Mumbai.