According to Huntington, the obstacles to democratisation for Islamic countries have been mainly cultural, most famously associated with his well-known Clash of Civilisation thesis. He divided the world into seven or eight civilisations, with one of them being Islam. Though he acknowledged that each civilisation has internal divisions and conflicts, it is not deep enough to prevent them from being a meaningful entity. Since then, all countries with a Muslim majority and an “Islamic” political system have been seen as fundamentally anti-democratic.

At its worst, radical Islam is identified as political Islam, and the entire religion is associated with violence and terrorism, resulting in labels such as Islamophobia. Islamophobia has been defined as “an exaggerated fear, hatred and hostility towards Islam and Muslims, perpetuated by negative stereotypes resulting in bias, discrimination, and the marginalisation and exclusion of Muslims from social, political and civic life”. A clear example would be the treatment of Muslims in America and Britain after the terrorist attack of 9/11.

We looked at 45 countries with a majority Muslim population (≥ 50%) across 20 different indicators, ranging from population of Muslims, ethnic fractionalisation, religious diversity, democratic performance, governance and stability, and economic indicators. We essentially saw three big groupings, barring a few exceptions, among these countries based on their current democratic performance and transition in their political systems.

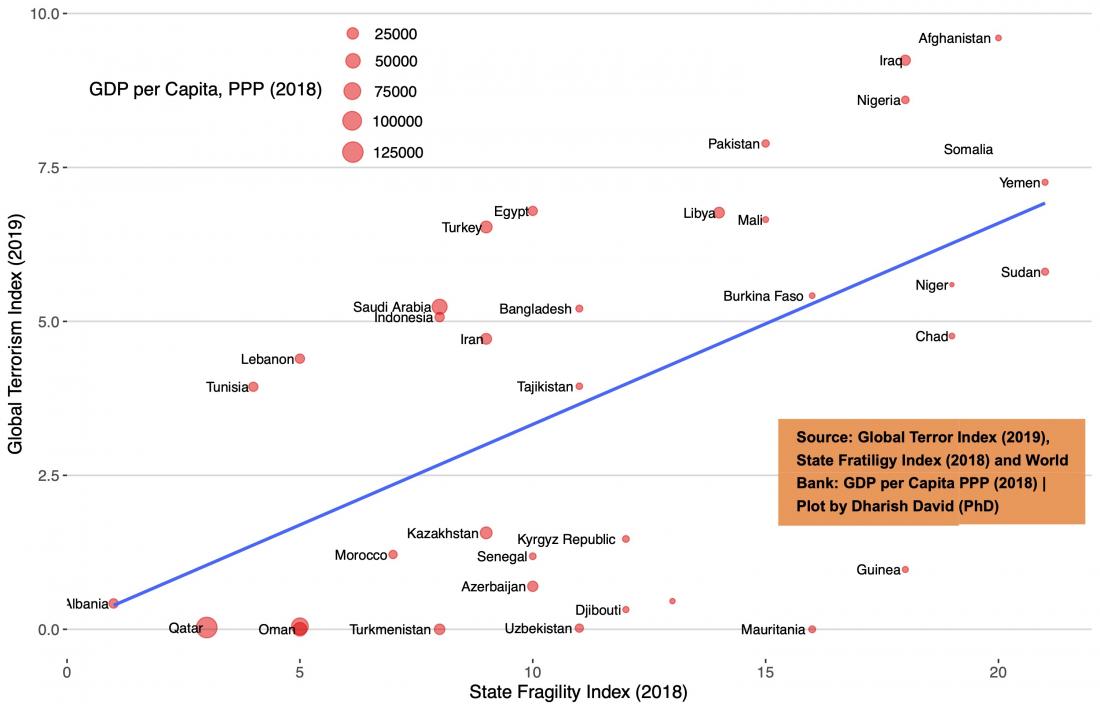

Fragile States in the Middle East, South Asia and Africa are also terror hubs

The first group consists of unstable and fragile states, most familiar in mainstream media that sometimes likes to equate political Islam with this sort of radical Islam. A lot of its proponents are based in war-ravaged and post-conflict countries ranging from Afghanistan in South Asia, and Iraq, Yemen, Libya and Syria in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, extending to a host of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Nigeria, Somalia, Mali and Sudan. Unsurprisingly, these states also ranked the highest on the terror index.

A common trend among these countries is the strong presence of non-state militant groups like the Talibans, ISIS, Al-Shabab and Boko Haram, who also control parts of these countries. They too share a common identity and goal. Despite that, these conflict-ridden, or rogue-ish countries are only a few among the more stable states with a Muslim majority population.

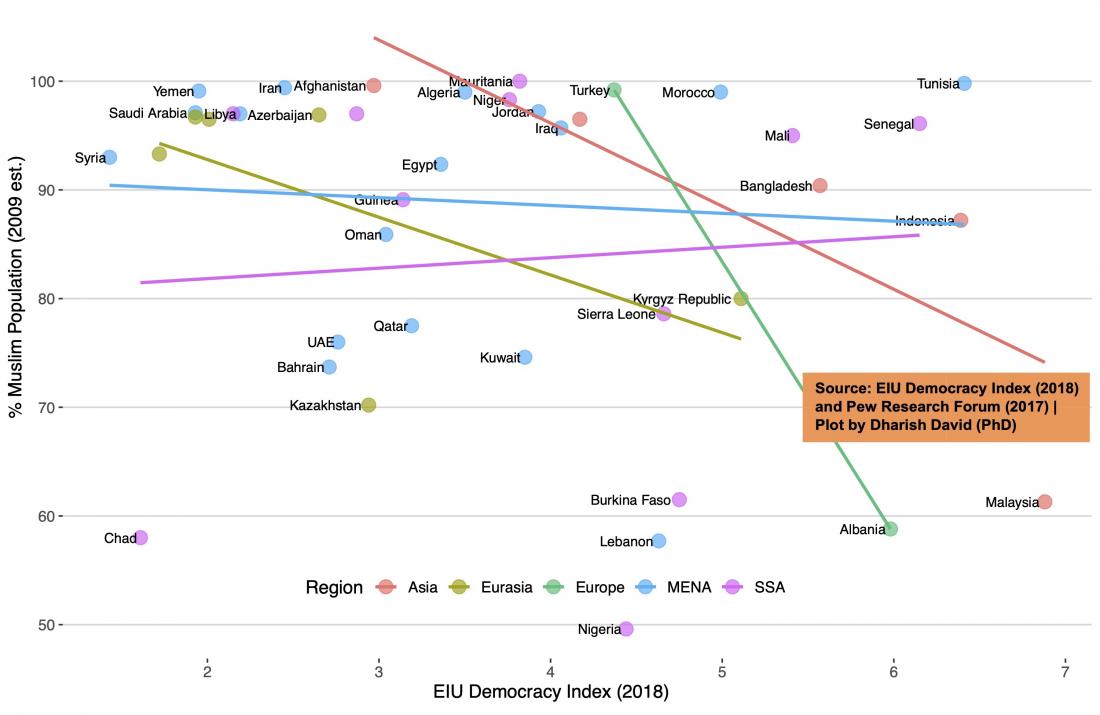

Among all Muslim majority countries, there is also a range of variation to consider, such as geographic location, cultural circumstances, political, economic, and democratic performance. A distinct feature that separates the democratically-driven Muslim majority countries from the “content authoritarian” countries is in fact, culture and diversity, as well as wealth. Not only do wealthy oil-rich autocratic states not tax their people, burying the organic expectations of holding the government accountable, they too provide a wide range of good quality public goods and services, distributes benefits and create jobs for its people, keeping them satisfied and politically passive. Though there are exceptions, in general, we do find that the larger the percentage of Muslims in the country, the weaker their democratic performance.

Stable autocracies in the Middle East endowed with oil and resources are in no hurry to democratise

During the initial Third Wave of democratisation, since the mid 1970s, there were hopes that democratisation would spread to many Muslim majority countries. However, to date, the Middle East has seen the least rates of democratisation, though many of its countries are quite stable autocracies. These are the second group of nations. They are the most autocratic, and the epicentre of cultural Islam. They too are quite well endowed with oil and gas resources, and are also overly dependent on these forms of revenues. Morever, these regimes, unlike other Muslim majority countries, also have a refined secret police and intelligence apparatus to help them hold on to their power and position in the political realm, undermining civil and political rights. A large proportion of countries in this group are located in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, which is known for their religious and ethnic homogeneity, with a few outliers.

For countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, radical interpretations of religious texts and harsh implementations of law and order are in place. They have a fierce intolerance to any form of criticism or democracy – both political participation and liberal rights. These countries are also known for infringing on civil rights, and obviously score lower in democracy indexes, such as the EIU Democratisation Index. Saudi, for example, with its two undercurrents of political Islam, the Muslim Brotherhood and political Salafism, grapple with the reluctance to modernise the society and providing for progressive aspirations linked to individual civil rights. Particularly, Saudi Arabia’s political role as a custodian of Islam’s two holiest sites, and where religion began, is being questioned for not taking up the issues that affect Muslims worldwide.

What is worth noting is that in spite of such violations of human rights, these states face little pressure from the West due to the oil partnership they have with them, in addition to the influence they have over global oil prices as the world’s swing oil producer. This alone gives them considerable authority in the international community, on top of Saudi’s sovereign wealth fund “Public Investment Fund” investing in US’ infrastructure programmes, and their own oil money used as venture capital put into Silicon Valley’s own Vision Fund; not forgetting how they are the biggest arms customer to the US. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia has significant influence over policies of states within the Muslim world, with key Muslim leaders unwilling to fall on the wrong side of the Saudi leaders, as exemplified by the leaders who boycotted the Kuala Lumpur Islamic summit last December over the issue of appropriate organisation overlooking this summit.

There are a few outliers though. Lebanon is an interesting case in the Middle East, which has a significant civil liberties score and a similar share of Muslims and Christians accounting for the religious diversity. Women too have political rights equal to that of men, as well as representation in government. People are free to practice the religion of choice with some restrictions on part of the community.

Another two well known exceptions in North Africa are Algeria and Tunisia, though they are more homogenous in ethnic and religious terms, they have been able to push for more civic liberties. In Algeria, there is limited academic freedom, freedom of speech with common limitations such as libel and slander, and restrictions on freedom to assemble that is inconsistently implemented.

Tunisia, as the sole beacon of democracy in MENA after the Arab Spring in 2011 is also the only country rated as “Free” by Freedom House among Muslim countries. It has been working towards sustainable democracy where political competition is respected, citizens are encouraged to participate in political decision-making and have freedom to demonstrate. In addition to that, the constitution ensures that the people have a right to the freedom of belief and exercise of religious practices of their own religions within their places of worship. Tunisia is also in the forefront of women’s rights in the Muslim world, and it has a free press allowing for press competition. One of the more important points to note is that there is an absence of foreign intervention and interference.

Muslim Eurasia too is autocratic, drawing some of its legitimacy in preventing radical Islam

Muslim majority countries in Eurasia can also be grouped here, not necessarily for their strong Islamic interpretations onto their political systems, but for being a part of the Soviet totalitarian regime in the past, which makes the transition to democracy quite problematic. The states in Central Asia, including the top three in terms of democratic performance – Kyrgyz Republic, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, face a conundrum as the link between the West and the East, pursuing staunchly authoritarian in continuity with their Soviet past, and a repressive hand over conservative Islam and basic human rights. Ironically, this has created a conducive environment for Islamic radicalisation, but also the underdevelopment of their own societies with early demagogues damaging the foundations of democracy, creating a heavy reliance on natural resource revenues or remittances. Furthermore, with unclear territories drawn, minority groups are left out of nation-building while the areas of jurisdiction are inconsistent.

The Kyrgyz Republic has religious homogeneity, unlike its Eurasian Muslim majority counterparts, but it does have ethnic diversity, with an almost three quarters majority being the Kyrgyz – 74%, and minority Uzbeks – 15% and Russians – 6%. There is a working parliamentary system with protected democratic institutions and significant efforts to promote human rights in the country, but they have a long way to go in providing minorities rights while they also struggle to build a proper national identity.

For Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, their democratic institutions are not strong enough to withstand the civil liberties violations faced by their people. In Kazakhstan, even the most basic of free and fair elections are not successfully carried out due to political control and obstructions put in place by the government. There may be freedom of religion but what is codified is not necessarily put into action on the ground. In Uzbekistan, the situation is even more dire. Its ethnocentrism ultimately led to a trend of emigration among non-Uzbeks who lived there, creating a vacuum for Islamic militants to infiltrate and grow. There is zero press freedom, and internet blackouts are used as a tool by the government before 2019. Though religious diversity is provided on paper, severe restrictions are imposed on religious minorities. Limited academic freedom has been a part of the government for a long time, and many other basic freedoms are suppressed.

In other regions of the world there is an attempt to make Islam more compatible with democracy

The third group of countries are generally found in Asia, Europe and Africa, that have made considerable progress because they want to prioritise democracy that mainly include political and civil freedoms. Some examples are embracing free and fair elections, providing for individual and minority rights, fair competition among political parties, and freedom of religion. Unlike in MENA and Eurasia, particularly the oil-rich Arab countries, these regions are less reliant on oil rents as a source of revenue. Instead, they have a taxation system which calls for good governance through democratic means to accumulate and redistribute wealth for the development of their country. By having a taxation system, citizens can hold their governments accountable. In addition, these regions are more ethnically and religiously diverse.

In Europe, Turkey and Albania’s democratic pursuit had been influenced by the European Union (EU) as well as Turkey’s (EU) membership candidacy and Albania’s economic transition and strengthening of its integration with the EU. Though they both have high ethnic homogeneity, Albania is more diverse in terms of religion, whereas Turkey is more homogenous. Interestingly, this difference mirrors a divergence of civil rights between these countries. While Albania has strong civil liberties, Turkey’s democracy has faltered over the years due to Erdogan administration attempts to make Turkey a more religious state. In Albania, there is academic and religious freedom and freedom to assemble. Religious minorities also have the freedom to their own rights, since the state is secular, though ethnic minorities are significantly more vulnerable to political exploitation. Meanwhile, in Turkey, media independence has dwindled and is more state controlled. The freedom to practice religion is also further suppressed due to limited access to resources. Academic freedom has, for a very long time, not been adhered to, and freedom of expression is rather restricted to private space.

Sub-Saharan African countries are diverse in terms of ethnicity and religion, which reflects on their civil liberties and democratic scores. Although these countries have a low GDP per capita and in spite of higher percentage of a Muslim population, there are more countries scoring higher on both civil rights and democratic performance. Senegal may face some political instability, but there has never been a successful coup or harsh authoritarianism in place, signifying a sounder democratic institution. Senegal is also moving towards gender equality. Mauritania recently adopted constitutional reforms that allowed for better ‘free and fair’ elections to take place. There is a significant level of press freedom, freedom to education and guarantee of freedom of assembly. Niger has allowed the freedom to participate politically, improved its women representation, and there is academic and press freedom; though there may be unwritten consequences.

Majority of the Muslim population live in South Asia and Southeast Asia. Among them are Indonesia, Malaysia, and Bangladesh, who ranked the highest in terms of democracy and civil rights, compared to other Muslim countries, due to the presence of larger ethnic and religious minority groups. These countries have also integrated democratic principles into the society’s fabric. Indonesa is home to 300 ethnic groups (including the majority Javanese – 40% and the Batak – 16%), and has 6 officially recognised religions including Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism. Practicing any religion not officially recognised is forbidden. The concept of Pancasila also enabled a depoliticised multiracial and multi-religious society to form, creating a more tolerant and understanding society.

Malaysia is multiracial and multi-religious too with 3 main ethnicities, including Malay, Chinese and Indian, with a Muslim majority and significant minorities practicing Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism and Confucianism. Religious tolerance and harmony are not only encouraged, but also become the foundations for the culturally diverse country. Through the intermixing of relations, Malaysians too grew more tolerant and understanding of differences, though their society still has a long way to go in reaching its goals of guaranteeing its minority full rights.

Bangladesh is most homogenous compared to Indonesia and Malaysia in both aspects of ethnicity and religion. Muslims make up about 89% of the population, alongside Hindus, Buddhist and Christian minorities. Approximately 98% of their population identifies as Bengali, though there are 27 other ethnic groups. Rather than promoting a multicultural image, they focus more on the understanding between its people, the socio-political and economic goals of that country, and the acceptance of its diversity in its history.

Majority of the Muslim countries are in transition

Although it may be quite convenient to group all Muslim majority countries together, branding them as anti-democratic does not provide the larger picture as there is quite a lot of variation in regional and individual country’s democratic performance. Religious diversity is particularly crucial in ushering in and sustaining democracy.

By itself, Islam is not monolithic, but the democratic transformation process in the Islamic world continues to face controversies and contradictions. Non-Arab Muslim majority countries, as opposed to oil-rich Arab countries, are more democratic and value the importance of civil rights. What sets the groupings apart are the level of tolerance, openness and acceptance of pluralism. A pluralistic and integrated society also encourages the role of reasoning — something that is lacking in fragile and authoritarian Muslim states, propelling some degree of understanding between the people the appropriate role of Islam in the public sphere.

Societal beliefs and attitudes that vary with time and generation also play a part in finding the right balance. Over time, political Islam will evolve with a new generation who prioritise a more liberal outlook vis-a-vis their older generations. Even in autocratic MENA, there has been a revolutionary call for democracy, as seen in the Arab Spring (though it failed in many countries). Given the fact that over 50% of the Muslim population lives in countries in transitioning flawed democracies and hybrid regimes (ie. Indonesia, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Nigeria) instead of authoritarian ones, it seems quite an exaggeration that Islam and democracy are completely incompatible.

Dharish David (PhD) is an associate faculty for the University of London at the Singapore Institute of Management – Global Education (SIM-GE), teaching courses relating to political economy.

Nur Farwizah Adlina Binte Mazlan, Undergraduate Student in International Relations at the University of London, Singapore Institute of Management – Global Education (SIM-GE)

Nur Amirah Binte Abdul Manan, Undergraduate Student in Economics and Politics at the University of London, Singapore Institute of Management – Global Education (SIM-GE)