The UN-FAO report, “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World”, published in 2022, highlights certain glaring concerns with global hunger and poverty that could jeopardize the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals of “no poverty” and “zero hunger”. The unusual COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and its persisting effects in 2021, represent a massive impediment to assessing the global situation of food insecurity. Despite expectations that the COVID-19 pandemic would be over in 2021 and that food security would gradually improve, global hunger surged in 2021. The prevalence of undernourishment (PoU), which had been essentially constant since 2015, increased from 8.0 to 9.3 percent from 2019 to 2020 and then increased more steadily to 9.8 percent in 2021.

More than half (425 million) of the world’s undernourished (768 million) people live in Asia, while more than one-third (278 million) reside in Africa. Latin America and the Caribbean make up around 8% of the world’s undernourished population (57 million). With 40.6% of the population experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity in 2021, Southern Asia is the sub-region of Asia with the greatest rates of food insecurity. Despite a 2.6 percentage point decline from 2020 to 2021, this represents a rise of around 6 percentage points since 2019 and more than 13 percentage points in five years.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations estimated that 3.07 billion people globally were not able to afford decent food in 2020. Nearly one-third of this population resides in India, the second-most populous country. The research additionally notes that the economic crisis spurred on by the COVID-19 pandemic and by the measures used to contain it disproportionately affected vulnerable sectors of the population, such as women, youth, low-skilled workers, and those in the informal sector.

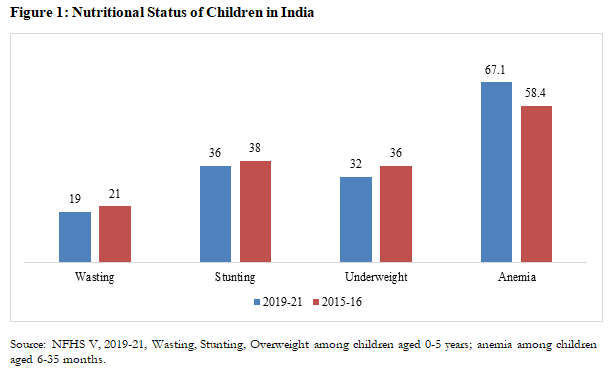

Coming to India, over 970 million Indians, or roughly 71% of the population, are unable to afford nutritious food, compared to several 43.5% for Asia worldwide and 80% for Africa, according to a cross-country comparison on the affordability of healthy diets. For instance, in India, there were 224 million people who were undernourished in 2019–21 or 16.3 percent of the population. This is further illustrated that, between 15 and 49 years old, 53 percent (187 million) of Indian women were anaemic. According to the NFHS-V, 2019–21, children in India also experience various types of nutritional deficiencies.

Figure 1 demonstrates how India has managed to lower the percentage of wasted, stunted, and underweight children during the past five years. However, the percentage of children who are anaemic currently has sharply increased (9%). This is a troubling development for the country, which is partly attributable to the fact that more than half of women of reproductive age also have anaemia.

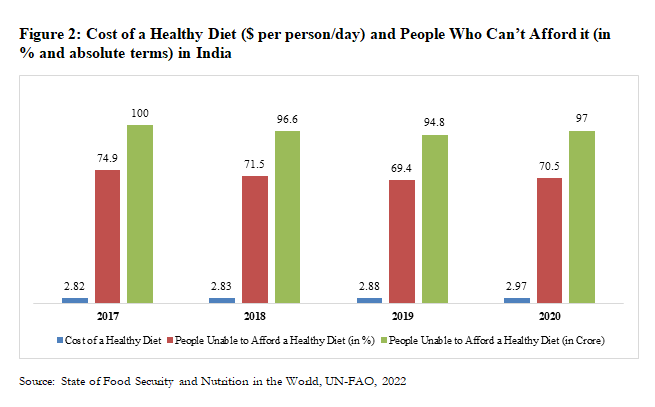

The expense of a nutritious diet and the percentage of those who cannot afford it are two extremely significant outcomes that the report highlights across countries. Out of the 3074 million people in the world, 973 million Indians cannot afford a nutritious food. This figure is alarming and concerning because Indians make up almost one-third of the global population who cannot afford healthy diets.

Figure 2 demonstrates that in 2020, 70% of Indians did not have access to a healthy diet. Since 2017, this figure did not significantly decline. This is a counter-intuitive result when this number is compared to the price of a nutritious diet. For instance, in 2017, the year with the lowest cost of a nutritious diet, 75% of Indians could not afford one, the highest percentage in the preceding four years. To put it in another way, the cost of a healthy diet was relatively low as compared to the other three years. The cause of this may be because, despite the reduced cost of obtaining a healthy diet, individuals are either uninformed of healthy food owing to a lack of education or they have other areas of expenditure, such as housing, clothing, sanitation, etc., or both.

According to NFHS-V, 23% of women in the reproductive age group had no formal education. Additionally, despite the fact that consumers continued to spend up to 28.3% of their total private final consumption budget on food and non-alcoholic beverages in FY19, many people poor dietary practices. Healthy and nourishing foods including fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains critically lacks in their diets.

It stands to reason that a large number of people cannot afford a nutritious diet due to its higher cost. If the cost of a healthy meal exceeds 63% of an individual’s income, they cannot afford it, according to Food and Agriculture Environment, i.e., to assert that high inflation makes a balanced diet expensive. As noted, the consumer food price index inflation has increased by more than 300% over the past year, making a balanced diet unaffordable for even more people.

The COVID-19 made it increasingly challenging for people around the world, but especially for Indians, to pay for increasing consumer food costs because of job losses. The negative impact of the COVID-19 on the market and the economy is yet to be fully restored making it even more difficult for a sizable portion of Indians to afford healthy meals in the face of growing food prices and job losses. One of the causes of the growth in the proportion of individuals who will not be able to buy a nutritious diet in 2020 is this decline in the purchasing power of Indians (measured as the composite of real income and the price of goods).

In future, if the growing food prices are not matched by rising income, more people will be unable to afford a healthy diet. If food prices rise while incomes fall, the upshot could be that even more people find healthy diets unaffordable. It is critical for the Indian government to continue funding food security programs that were launched prior to and throughout the pandemic era for some time until the market fully recovers. Additionally, the informal sector, which now employs 47.6% of the workforce (down from 53.5% before the epidemic), had a significant decline in employment, which had a negative impact on the income of millions of Indians. The need for the government to develop a micro-level recovery plan for the informal economy is extremely important. In order for a significant portion of Indians to be able to generate a steady income to spend on a healthy diet, it is also crucial for the government to support the formal sector’s industries with new stimulus measures in addition to the earlier ones or by lowering interest rates (with a caveat, of course).

*Shatarupa Dey is a Ph.D. Student at the University of Utah, Department of Political Science. Twitter handle: shatarupadey95. Dr. Prashant Kumar Choudhary is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Public Policy, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), Bangalore, India. Twitter handle: edition_india