ABSTRACT

At a moment when President Donald Trump’s “America First” isolationist rhetoric threatens to result in a voluntary self-retreat from an international system which the U.S. helped to shape, potentially reducing its relative political and economic weight, other relevant actors are expected to undertake efforts to fill the international void left by an apparently shrinking superpower. China and Russia are among the usual “suspects” that could profit from the American retrenchment to stake their claims to a greater global role. Likewise, changes unleashed by an eventual American retreat might herald a new era in which the BRICS, under the Chinese leadership, could aspire to become more influential in world affairs, helping to reshape, keep, and promote international institutions, norms and regimes in an increasingly multipolar world. Within that context, China seems to value its BRICS membership due to three main reasons: i) as a geopolitical cover, to disguise its unilateral actions; ii) as another instrument to counterbalance U.S. power; iii) as a platform to advance other Chinese geostrategic interests.

INTRODUCTION

In his classical book Tout Empire Périra, the renowned French historian Jean-Baptiste Duroselle (1981) presents his bold, although controversial, theory of the rise and fall of empires, according to which a nation´s power is the result, among other variables, of the way that state interacts with other actors in the international system. Duroselle argues that, as the sources of domestic power of a nation are not permanent or immutable, and as the nature of the interaction between actors of the international system can suffer dramatic changes, the power of nations tends to erode over time, and its decline becomes irreversible.

Although from a different perspective, Paul Kennedy (1987) resumed that debate in the late 80´s with his blockbuster book, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, which sought to analyze and explain the causes of the relative decline of American power. While alerting to the growing questioning of the United States´ leadership role in the world, in a context of decreasing economic performance and serious geostrategic challenge posed by a rapidly-growing Japan, then the world´s second-largest economy, Kennedy´s work was based on two premises. First, history shows that all great powers in the modern Westphalian international system have experienced the same pattern of emergence, rise, apex of their power, and then relative decline. Second, this general pattern highlighted the fact that no great power has managed to remain the dominant player ad aeternum, and the United States would be no exception to this rule.

Despite the virtues – and flaws – of these two must-read reference books, none of them dealt specifically, and in a concrete way, with possibly impending changes in the hierarchical structure of the international system of states, geostrategic disputes, new opportunities for international insertion, and the observance of international norms and regimes. The analysis of such issues is extremely relevant at a moment when President Donald Trump’s “America First” isolationist rhetoric spreads into the national agenda, creates global uncertainties, and threatens to result in a voluntary self-retreat from a liberal international order which the U.S. helped to shape and which enabled that country – and most of the world – to grow and thrive. Such move could potentially reduce the relative political and economic weight of the United States, and gives renewed vigor to the ideas of Duroselle (1981) and Kennedy (1987).

In that context, other relevant actors are expected to undertake efforts to fill the international void left by an apparently shrinking superpower. China and Russia are among the usual “suspects” that could profit from the American retrenchment to stake their claims to a greater protagonist role in world affairs. Such changes in the international system might also herald a new era in which strategic groupings, such as the BRICS, are expected to not only wield greater influence in the global arena, but also to reshape and revamp international institutions, rules, and regimes in order to align them to emerging power realities in a more multipolar world.

More than provide a critical account of the BRICS as an analytical category, this paper seeks to discuss why China values the role of the BRICS, seen as one of the several key mechanisms Beijing can use to push forward its view of a different world order, while crafting a more highlighted global leadership role for itself. In doing that, this article incidentally examines some of its constitutive dimensions, weaknesses and vulnerabilities, with a main focus on the political and economic relations among its members, within the context of current debates on paradigm shifts in the global political economy. The objective is to analyze whether the possibilities of an effective multilateral intra-group cooperation are real and whether this multilateral cooperation could lead to a major change in the world power distribution, or if, on the contrary, the stresses, strains, and contradictions on its structures indicate that the BRICS forum is running out of steam. In such case, the group’s collective clout would be more a piece of conceptual wishful thinking than a real game-changer, or, alternatively, an asset used primarily to back up the aspirations and interests of one of its members.

THE RELATIVE POWER OF IDEAS

There is no doubt that acronyms can be a highly valuable instrument of marketing, by creating a powerful abbreviation for something meaningful and establishing a connection with positive associations, giving them meaning, context and value. The problem with thinking in terms of acronyms, however, is that “once one catches on, it tends to lock analysts into a worldview that may soon be outdated” (Degaut 2015), which might be the case with the BRICS.

In other words, the original justification for the creation of the acronym would be related to the extent to which those countries could – in a moment when the emergence of the so-called “rising powers” seemed to captivate all the attentions of the foreign-policy audience – have an impact upon the global economy, which is understandable, considering that the BRICS make up nearly 43% of the world´s population, a fifth of the world´s gross domestic product and 17% of the global trade. Nevertheless, Almeida (2009) notes that “this aggregation of individual volume might make sense in this type of intellectual exercise, in which arithmetic seem to prevail over politics. However, it is unlikely to indicate global economic development trends, as these are caused by technological transformation and capital, scientific and strategic information flows”.

Reality is rarely so sunny, however, and the intricacies of foreign affairs are significantly more complex than the rhetoric of changing the global political architecture would have people believe. In spite of the vast resources and capabilities of its members, when individually considered, the BRICS have yet to make significant progress toward building a collective identity or an institutional apparatus after nine summit meetings. With the exception of the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Contingency Reserve Arrangement (CRA), which are tangible accomplishments, the mechanism has failed to give more visibility to its initiatives and to group them together within the framework of a strategic agenda. The next sections will examine some of the association´s still existing deficiencies and the possible reasons why the BRICS should not yet be discarded as a useful collective instrument for pursuing common foreign policy objectives and interests. Such platform has the potential to allow its members to cause a real global power shift – eventually rendering anachronistic old concepts such as North and South, and East and West – and to make them benefit in tandem more from shifting global power relations and eventual paradigm changes.

WHAT COULD BE DERAILING THE BRICS?

A number of variables have been preventing the BRICS from building a more convincing narrative about their role in reshaping global economics and politics. Most analysts have concentrated their criticisms almost exclusively on economic aspects and judged the association by their economic growth (or lack of). The main argument is that the initial hype and euphoria with which the group was initially received, due to their then stratospheric growth rates, would no longer be valid today, in part due to a combination of changing global circumstances, which included the end of the commodity super-cycle, and domestic contingencies.

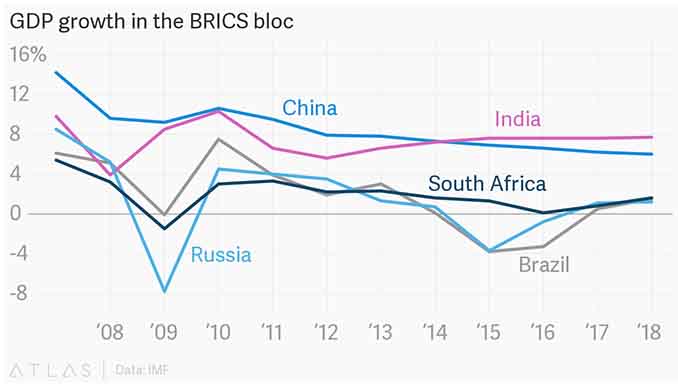

In fact, GDP growth in Brazil, Russia and South Africa is experiencing a significant downward trend in recent years, as can be seen in Table 1 and Figure 1. Brazil and Russia are still facing a persistent economic slowdown. China´s economic performance remains relatively steady, but it has recorded its lowest growth rate in decades, as the country seeks to implement structural reforms to shift its central growth drivers from foreign demand for exports and investment to domestic consumption. India remains the world’s fastest growing economy, advancing 7 percent in 2016. Although that number seems high, it has to be noted that India´s GDP annual growth rate averaged 6.10 percent from 1951 until 2016[1], which is not enough to promote sustainable and largely inclusive development in a country where nearly 33 percent of the population still falls below the international poverty line of US$ 1.25 per day, and nearly 70 percent live on less than US$ 2 per day[2], despite the government´s systematic efforts to overcome that situation. In other words, as China and India are the only BRICS countries currently worth of the title and three out of five BRICS countries are experiencing slow growth or recession in their economies, it seems that there is no reliable indicator, at this moment, to support the thesis that the BRICS tend to become the engine of global growth.

Table 1. BRICS Growth Rate in percent, 2010-2017

| Country | 20101 | 20111 | 20121 | 20131 | 20141 | 20151 | 20162 | 20173 |

| Brazil | 7.5 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 0.5 | -3.8 | -2.5 | 0.9 |

| Russia | 4.5 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 0.7 | -2.87 | 0.3 | 1.7 |

| India | 10.3 | 6.6 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 7.0 | 6.7 |

| China | 10.6 | 9.5 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.7 |

| S. Africa | 3.0 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

Source:

- World Bank GDP Growth (annual %), [http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG].

- Trading Economics, [http://www.tradingeconomics.com/forecast/gdp-annual-growth-rate].

- World Bank GDP Growth projection (annual %), [https://data.worldbank.org/country/].

Figure 1 – GDP Growth in the BRICS

As a recent paper argues, “in the global race for economic success, GDP has come to count more than any other factor, which explains why analysts believe that, by sustaining high rates of GDP growth, the BRICS countries are likely to generate a fundamental power-shift in global governance institutions” (GovInn 2014:3). Measuring the BRICS´ success solely, or mainly, through GDP growth rates, however, is not only unfair, but also mistaken. Likewise, assessing the group´s potential based on apparently shared characteristics such as exposure, at different levels, to corruption, high rates of illiteracy, poverty, regional income and economic inequalities, overexposure to commodities and dependence on commodities exports, dependence on foreign direct investments, institutional weakness, vulnerability to asset bubbles, poor institutional and regulatory quality, and a relatively small opening to the global economy seems equally wrong. After all, since many of these characteristics can usually be attributed to most developing countries, they can be considered neither defining features of the BRICS nor indicators of its capabilities.

Considering that the BRICS want to be seen as a platform for dialogue and cooperation among its members, not only in economic, financial and development domains, but also in the political sphere, the group´s problem, perhaps, lies essentially in the fact that each of the countries has entirely different strategic cultures. This is no irrelevant matter, as the foreign policy goals that are to be pursued by a state, which reflect its identity, interests and priorities, are to a large extent defined by its strategic culture. For the purpose of this study, and at the risk of oversimplifying a complex issue, strategic culture can be understood as a deeply held cultural predisposition for a particular strategic behavior or strategic thinking. In this same line of thought, the United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) defines strategic culture as “the combination of internal and external influences and experiences – geographic, historical, cultural, economic, political, and military – that shape and influence the way a country understands its relationship to the rest of the world, and how a state will behave in the international community” (Bitencourt and Vaz 2009:1).

This concept highlights the idea that strategic culture is a product of historical experience. Since these experiences differ across states, “different states have different predominant strategic preferences that are rooted in the early or formative experiences of the state, and are influenced to some degree by the philosophical, political, cultural and cognitive characteristics of the state and its elites” (Johnston 1995:34). The approach helps to explain “what constrains actors from taking certain strategic decisions, seeks to explore causal explanations for regular patterns of state behavior, and attempts to generate generalizations from its conclusions” (Degaut 2017:274).

In other words, what is being advanced here is that, possibly due to their different strategic cultures, the BRICS countries have distinct worldviews, foreign policy priorities and interests, diplomatic practices and preferences, and international insertion models and instruments. In consequence, while they do seek to periodically meet as a group to coordinate their positions, they have yet to undertake greater efforts to surmount those differences and establish a political community united around a common agenda. Their diverse, and oftentimes divergent, interests have rendered them unable to forge a common denominator on important issues such as climate change, human rights and humanitarian intervention, conflicts in the Middle East, terrorism, nuclear proliferation, and global economy and trade.

As an illustrative example, while Brazil, India and South Africa have sought to support a progressive agenda in the human rights dimension, China and Russia have methodically opposed it (Laskaris & Kreutz 2015). Likewise, and in line with their historical traditions, Brazil and India have stressed the need to respect sovereignty and ensure the territorial integrity of regions in conflict, which led them to abstain on the 2011 United Nations Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force against Libya’s Muammar al-Qaddafi. Those two countries, as well as South Africa, have adopted a rather cautious stance to the civil war in Syria, in contrast to Russian active involvement in the conflict, which “generates new tensions for the coalition´s discourse of sovereignty” (Abdenur 2016:111).

In the same vein, initial talks aimed at establishing a BRICS Defense Council, a forum envisaged to serve as the cornerstone of a future military alliance, have shown certain level of disagreement between those countries regarding security and defense issues. The idea of a military forum is advocated by Russia, which seeks with this initiative to counterbalance American influence in the UN system and, more particularly, NATO’s expansion and operations. Chinese policymakers do not rule out the initiative, which might be put into the framework of the strategic competition with the United States. They are still assessing, however, to what extent such defense council might end up undermining its well-established position in the UNSC and its ambition to occupy more prominent roles in the UN system.

India and South Africa, on the other hand, seem to discard the idea, for a number of different reasons. First, an element of regional rivalry cannot be disregarded (Cooper & Farouk 2016). India and China are at odds over a number of vital issues, including terrorism, Beijing’s aspirations in the South China Sea, and competition over influence in states as Cambodia, Nepal, Myanmar and neighboring regions, as well as New Delhi’s efforts to strengthen its regional position through enhanced relations with the United States and Japan. China’s posture on the South and East China Sea distresses not only India but also its ASEAN partners, with which India has sought to keep more cooperative relations. Especially unnerving for New Delhi is China´s strategic alliance with Pakistan. The geopolitical rivalry has led Beijing not to officially endorse India’s claim for a U.N Security Council seat. In return, India has persistently blocked the admission of China in the IBSA initiative, a political consultation forum made up by India, Brazil and South Africa.

In its turn, South Africa, which unlike other BRICS countries does not appear to be currently increasing the role and size of its armed forces to highlight its place as a regional power through rearmament, seems to reject the idea, on the grounds that it would probably be pointless and counterproductive, serving only to weaken international law. Brazil neither endorses the proposal directly nor rejects it. On the contrary, the country tends to analyze the issue in the light of its own national interest, and not based on any ideological affinity or collective agenda.

Certainly, some degree of cooperation in military and security affairs is possible and it is actually taking place, particularly in issues like cyber-security, intelligence cooperation, and information exchange. However, three factors make the establishment of a formal defense council, security forum, or military alliance appears less likely in the near future. Firstly, given the fact that the five BRICS countries tend to substantially differ in their defense and security interests, most cooperation is still taking place on a bilateral basis. Secondly, they have still been ambivalent as to how to combine their regional priorities and commitments with their membership in the BRICS. And finally, diplomatic rhetoric aside, it is not possible to identify a single precise threat that could unite those five powers around a security project, apart from counterbalancing the so-called “Western hegemony”, a loosely defined term which seems to become increasingly devoid of any practical meaning, as the world gradually becomes more and more multipolar.

THE BRICS AND THE AMERICAN LEADERSHIP: THE EMERGENCE OF AN ILLIBERAL WORLD ORDER?

For generations, the United States has largely set the terms for the international system, seeking to shape it to reflect not only its own ideals, norms and values – which were to be embraced by democracies –, but also its interests. The liberal world order, based on the rule of law, global economic development, the strengthening of international institutions and regimes, incentives to freer trade, investment promotion and cooperation has had, simultaneously, as its main engineer, backer and beneficiary the United States. Now, at a time when the U.S. is apparently turning inward, and President Trump administration’s contentious “America First” foreign policy agenda seems to be redefining the concept of national interest – whose main premise is that international relations are a zero-sum game – questions have arisen about who would possess the attributes needed to potentially fill the vacuum power created if the U.S. eventually abdicates its global leadership role.

President Trump apparently believes that the U.S. is experiencing a sharp decline due to its behavior on the global stage, particular its commitment to alliances, and that the American-led liberal international order has failed his own people. He is urging other countries to assume a greater share of the burden, doing more and paying more, the reason why he is redirecting his agenda to domestic politics and to a narrower set of national interests.

It might not be unreasonable to argue that, to some extent, Trump´s foreign policy is, in its essence, a continuation of Barack Obama´s “leading from behind” philosophy, which implied a virtual abdication of global leadership. Such doctrine, for example, was intensely exploited by Russia and Iran to advance their influence in the Middle East, and to impose their protagonism on the Syrian crisis, to the detriment of American influence and interests.

Likewise, in one of his first formal initiatives, President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a project originally initiated by the George W. Bush administration to set high-standard trade rules with Asia-Pacific countries and praised as the largest multilateral trade agreement ever. Apart from economic considerations, the TPP was also designed to counter China’s increasing economic influence in the region, a move which was part of the U.S. high-profile “pivot to Asia” strategy.

However, Trump´s measures to overhaul the global regulatory mechanism that America has traditionally championed may have backfired. The U.S. withdrawal from the TPP did not result in the end of the cooperation mechanism, as some expected, as on March 8, 2018, Ministers and Senior Officials representing Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam announced the signing of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a free trade agreement which incorporates most of the TPP provisions. Although member countries still need to complete domestic processes to bring the mechanism into force, other economies, such as the United Kingdom, have shown a remarkable interest in acceding to the Agreement and are currently holding informal discussions on that matter.

Additionally, China – which has already emerged as the leading trade partner of most regional economies – is presently pushing forward a diplomatic initiative that can eventually lead to the establishment of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which also involves Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea and the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Such initiative can give China the opportunity to set the rules of trade in an area comprising over 60% of the world economy.

Not only that. China, the most powerful BRICS member, seems to be already taking advantage of the apparent American retreat to lay the first bricks of what could be a new era of globalization or even a new, and illiberal, world order. Through the launching of its ‘Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an ambitious development project estimated in over US$ 1 trillion, China seeks to spread its influence by boosting trade, providing massive funds for infrastructure building, and stimulating economic growth mainly, but not only, along the centuries-old Silk Road. The BRI, which counts with the Brazilian and Russian support, reflects and values China´s strategic option to strengthen economic and trade ties with the rest of Asia and Africa in order to foment their dependence on Chinese demand and investments. Such initiative, which seeks to leverage China´s economic capabilities into geostrategic power, seems to know no geographic boundaries, as it reaches as far as Europe – particularly on a number of investments and infrastructure projects across Eurasia – and Latin America.

To compound the situation, President Trump´s recent decision (March 2018) to adopt tougher, protectionist trade policies, by imposing steep tariffs on imported steel and aluminum from a number of important trading partners and by imposing tariffs on US$ 60 billion worth of Chinese imports a year and limiting China´s capacity to invest in the American technology industry has prompted threats of retaliation and boosted fears of a full-blown trade war.

Trump´s protectionist measures – some of which were based on a now rarely used national-security exception to the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules – could eventually trigger a domino effect that might lead to a global recession in the long run, by restraining exports, discouraging investments, and shaking business and consumer confidence. In the short term, however, their main unintended consequences would be to call into question and undermine the very foundations of the liberal order and push a weakened Europe and Latin America closer to China. Rather to “make America great again”, such policies could further contribute to shift the economic and strategic global center of gravity to the Indo-Pacific region and speed up the process of making China great again.

As the U.S turns inward, Beijing seems to be well aware of the opportunity to remake the international system according to its interests, in a scenario in which the BRICS platform can be instrumental to its purposes. China indeed seems to value its BRICS membership due to three main reasons: i) as a geopolitical cover, to disguise its unilateral actions, which usually entails greater international costs and risks; ii) as another instrument to counterbalance U.S. power, within the framework of a collective action, arguably contributing to reform and improve the global governance system; iii) as a platform to advance other Chinese geostrategic interests, particularly in the economic and commercial spheres.

One of China´s most emblematic attempts to take on a more assertive role on the global stage took place in March 2017, when Foreign Minister Wang Yi presented the idea of extending the oureach of the BRICS by inviting other developing countries and emerging markets to join the group as associates, under the banner of the BRICS Plus. The idea basically means to establish intensive partnerships with other apparently like-minded countries to turn the cooperation platform more inclusive and impactful. The idea seems to have been welcome, as more than 30 countries send over 400 delegates to take part in the BRICS Political Parties, Think Tank, and Civil Societies Organization Forum and the 9th BRICS Academic Forum, held in the Chinese city of Fuzhou from June 9 to 13, 2017.

Such diplomatic move does not contribute to deepen the group´s internal cohesiveness, but it clearly is a step forward in the process of expanding China’s geopolitical clout. By emphasizing an apparent multilateralism and operating within the framework of a collective action mechanism, Beijing can use the BRICS to attenuate perceptions that it is fundamentally seeking to challenge the international status quo, while quietly carving out a greater global role for itself in a new order it is seeking to build. One which, perhaps, is not entirely based on the same liberal values, principles and practices that the world got used to for the past seventy years.

None of those initiatives, however, can hide the fact that the U.S. is still a fundamental country for the stability of the current international order. Its economic, military or political capabilities have not declined significantly in qualitative terms, although its relative power and primacy in global politics seems to be visibly eroding. It is noteworthy, nonetheless, that certain triumphalism present in U.S. foreign policy discourse since the earliest phases of globalization seems to have disappeared, which, combined with a persistent slowdown of economic growth in the U.S. may have worn away America’s “will to power”.

These circumstances give renewed strength to initiatives towards promoting greater multipolarization of the world, in a context where strategic groupings, such as the BRICS are expected to attain more eminence. In fact, for much of the past decade, the steady rise of the BRICS towards such a preeminent position seemed an apparently irreversible fact. In the light of current economic downturns and diplomatic divergences among the grouping, however, evidence seems to indicate that narratives about such inexorable ascension might be exaggerated. And so are predictions about its inescapable decline.

What must be put in perspective here is that there are a number of misperceptions and misconceptions about the BRICS and its role. Perhaps the easiest way of defining the association is explaining what it is not and why it cannot offer more than it has to give. The BRICS is not an economic or trade bloc. It is not a deep integration process. It is not an alliance, in the classical meaning of the term. The BRICS is a platform for cooperation, one which is struggling through mistakes and successes to reinvent itself and follow innovative paths, so as to build an international environment that is more conducive to the achievement of the interests of its member countries. They do not want to fundamentally upend the table of the global order, but they want a better seat, while seeking to make that table more inclusive.

Although the shifting of global power may not be taking place as quickly as assumed, the current transition will likely prompt the main actors in the global stage to recalibrate their foreign policies and rebuild bilateral and multilateral ties, so as to pursue the stability of the international system and settle down into a pattern of relationships more adequate to an increasingly multipolar world.

In this scenario, the BRICS – looked down on by both the Obama and Trump administrations as a dysfunctional political arrangement – should not be entirely discarded, as it can still come to play a leading role in the global economy and the strategic landscape, despite its structural imbalances. Intragroup cooperation can provide each one of its members with an important platform to employ their collective clout for individual betterment. By acting together, however, that association can make a difference in world politics and global governance, particularly in issues more directly related to the immediate interests of developing countries. From this perspective, the apparent contrast between the potential rise of the BRICS and U.S. isolationist policies should not be seen within the narrow framework of a false dichotomy, but as a subject able to begin reshaping the international debate and painting a more realistic picture of the global distribution of power, especially when one major power such as China seems determined to build a new international order more conducive to its interests and commensurate with its resources, capabilities and appetite for greatness.

CONCLUSIONS

There is no doubt that, individually, the BRICS countries have been gaining weight and importance in global affairs and could be not, by any measure, be ignored anymore. Collectively, the association has the potential to be an important political partnership and diplomatic tool, having already championed a significant number of bold initiatives to foster multilateral cooperation and to reform the global governance architecture. Additionally, those initiatives could not only serve to change their relative position in the international order, but also be functional to the advancement of the national projects of its members.

Among these initiatives, the signature of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the NDB and the World Bank deserves attention. Signed in September 2016, the MOU seeks to strengthen their cooperation in addressing global infrastructure needs. But that is not all. The BRICS countries have been most active in the area of global economic governance, which includes the establishment of working groups to strengthen commercial, capital market, and development financial corporation to boost economic growth, to accelerate the internationalization of sovereign currency for a better international monetary system, and to reduce institutional and conceptual barriers to accelerate their technological and financial development (Wen & Ying 2017). Likewise, the establishment of their own rating agency is also being considered.

However, they are also boasting a sprawling set of working groups on a number of other important issues, like the enhancement of the status of the BRICS in the global value chain, which means turning resource-intensive industries and enterprises into labor-intensive, as well as manufacturing activities into high-tech value-added and knowledge-based creative activities. These groups are also undertaking studies on mechanisms to alleviate poverty, promote scientific and technological innovation, develop people-to-people exchanges, encourage cooperation on energy, food security and urbanization, create a University League, and establish a permanent Political Parties Dialogue Forum and a BRICS Travel Card.

These measures, however, are still considered limited in their depth, scope and acceptance, which to some extent reflect the group’s relative lack of cohesion, priorities, economic models, and foreign policy interests. Put into a larger framework, these variables are translated into the group´s difficulty to forge a consensus around a platform of collective action, and, consequently, their present incapacity to shape the international agenda

As ideas require coordinated and continuous effort to be translated into reality, and in order to reconcile speech and action, so as to take advantage of an eventual American retreat, the BRICS need to realign its cooperation prospects, an endeavor which depends mostly on five elements. First, political willingness to turn the mechanism into a real priority; second, ability and willingness to overcome and reconcile diverging interests and ambitions; third, ability to identify more areas of common interest that go well beyond what is already object of consensus; fourth, ability and resources to withstand the political and economic costs of countering U.S. power; and lastly, the adoption of more effective initiatives to deepen cooperation and develop strategic intragroup relationships, which means to translate the findings of the working groups into concrete proposals.

Without taking these elements into account, the BRICS will hardly be able to realize its full potential and will continue to be portrayed as a heterogeneous association of competing powers, a mere bargaining coalition or even an alliance of convenience, rather than what might come to be seen as the possible engine of a truly global power shift in the future. Perhaps more importantly, without addressing the asymmetry of power within the group and, more broadly, in global governance, the other BRICS countries might have to eventually agree to be demoted to the role of junior partners in the building of a new, China-led world order, if not serving as mere pawns in a larger global geopolitical game.

REFERENCES

Abdenur, Adriana (2016). ‘Rising Powers and international security: The BRICS and the Syrian conflict’, Rising Powers Quarterly, Vol 1(1), pp. 109-133.

Almeida, Paulo Roberto de (2009). ‘Trade and International Relations for Journalists’. Rio de Janeiro: Cebri-Icone.

Bitencourt, Luis, and Alcides C. Vaz (2009). Brazilian strategic culture. Finding Reports N. 5, Applied Research Center, Florida International University.

Brütsch, Christian and Mihaela Papa (2013). ´Deconstructing the BRICS: Bargaining coalition, imagined community or geopolitical fad?’, Chinese Journal of International Politics, Vol. 6, pp. 299-327.

Degaut, Marcos (2017). ‘Brazil’s military modernization: Is a new strategic culture emerging?’ Rising Powers Quarterly, Vol. 2(1), pp. 271-297.

Degaut, Marcos (2015). Do the BRICS still matter? A Report of the CSIS Americas Program, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, DC.

Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste (1981). Tout empire périra – Une vision théorique des relations internationales, Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne.

GovvInn (2014). On the BRICS of collapse? Why emerging economies need a different development model. Center for the Study of Governance Innovation, Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria.

Johnston, Alaistair Iain (1995). ‘Thinking about strategic culture’. International Security, Vol. 19, N. 4, pp. 32-64.

Kennedy, Paul (1987). The rise and fall of the great powers, New York: Vintage Books.

Laskaris, Stamatis, and Joakim Kreutz (2015). ‘Rising powers and the responsibility to protect: will the norm survive in the age of BRICS?, Global Affairs, Vol. 1(2), pp. 149-158.

O´Neill, Jim (2001). Building better global economics BRICs. Global Economics Paper 66, New York: Goldman Sachs.

Wen, Wang and Liu Ying (2017). The engine for new Globalization: Increase BRICS financial cooperation. Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Beijing: Renmin University of China.

[1] Trading Economics, India GDP Annual Growth Rate. Available at [http://www.tradingeconomics.com/india/gdp-growth-annual].

[2] World Bank, “Poverty & Equity: India,” 2015, see [http://povertydata.worldbank.org/poverty/country/IND].

Marcos Degaut, Ph.D. in Security Studies by the University of Central Florida, is currently serving as Deputy Special Secretary for Strategic Affairs in the Office of the President of Brazil and Research Fellow at UCF. He served previously as Assessor to International Affairs in the Executive Office of the President/Brazil, Deputy Head of International Affairs at the Superior Court of Justice, Secretary General of the National Judicial School, Political Advisor at the Brazilian House of Representatives and Visiting Fellow in the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR). Dr. Degaut has published articles in highly-respected outlets such as Intelligence and National Security Journal, Armed Forces and Society, Harvard International Review, Rising Powers Quarterly and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).