While Trump recently faced a lot of criticism for calling COVID-19 the ‘Chinese Virus’, his frustration could be understood when he stated that “if people would have known about it, it could have been stopped in place” before it spread globally. So the real question is whether Covid-19 could have been nipped in the bud, saving the world hundreds of thousands of lives and trillions of dollars, and how much of this is attributable to the control and centralization of a censored information environment in non-democratic regimes such as China?

To fully comprehend what happens in authoritarian states, it is important to look at democracies first, as they are based on the compact that citizens have access to reliable information requiring a free flow and open access to information from various distributed sources. In democracies, decentralised non-government actors are also instrumental in disseminating trusted information and debunking propaganda.

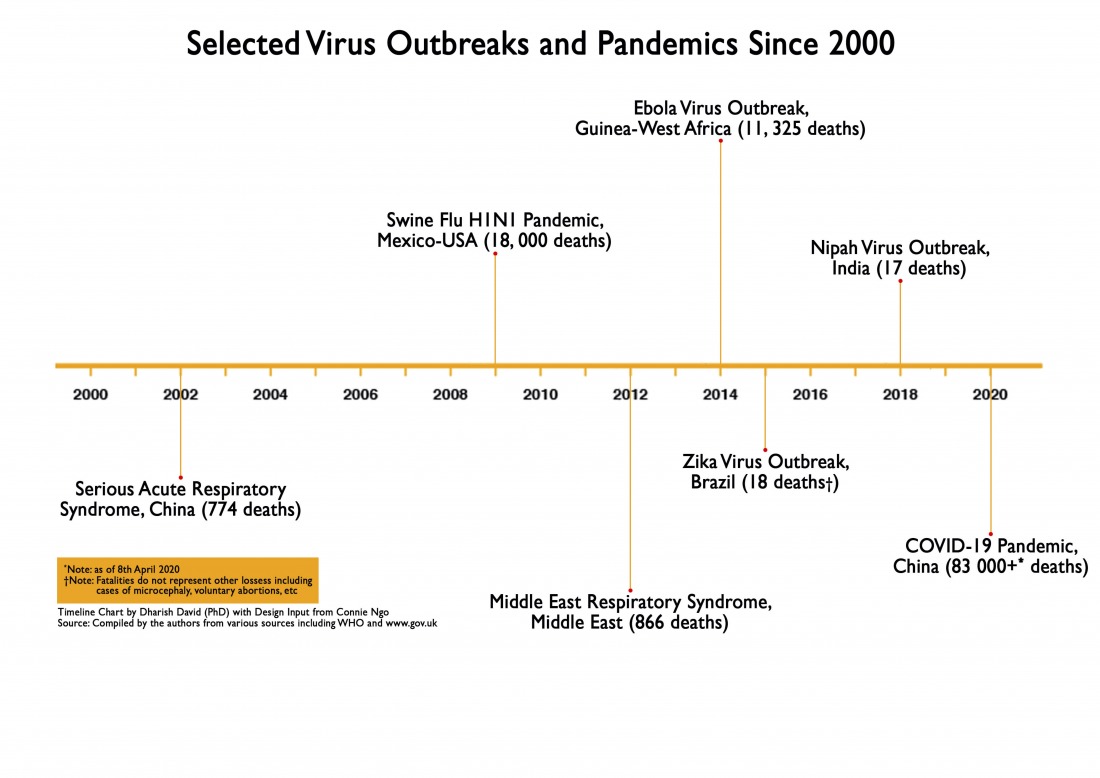

Early responses to communicable virus outbreaks provide us examples of the free and open flow of information in democracies in comparison to the information and narrative control prevalent in centralized autocracies. Since information flow is more open, accessible and distributed in democracies early warning signs of a crisis can be heeded, while authoritarian regimes may miss it by suppressing dissent and monitoring citizens in order to control the narrative through state propaganda.

While initially the Chinese government on 31 December 2019 reported a pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan, even the WHO subscribed to the view that there was no evidence of human to human transmission with a tweet on January 14. it took another three weeks for Beijing to admit that the novel coronavirus was spreading rapidly on January 21, and announced a full lockdown of Wuhan and Hubei province on 23 January. This came with an estimated lag of seven weeks since the virus may have started spreading, and millions were already moving in and out of Wuhan, especially in light of the Chinese New Year holidays. Ironically, China’s leading epidemiologist Zhong Nanshan, suggested that the success of the Chinese intervention mechanism was based on “The core points of the ‘four earlys:’ early prevention, early detection, early diagnosis, and early quarantine”, while the reality seems far different.

Soon after the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic on January 30, China was lauded for sharing information and containing the outbreak. China’s Great Firewall may have initially succeeded in controlling its domestic information narrative, but global criticisms came quickly. Beijing was charged with secrecy and suppressing information that challenged its domestic narrative and outbreak information from whistleblowers, limiting the capacity of China’s Centre for Disease Control (CDC), restricting WHO’s visits to Wuhan, and likely undercounting infections and deaths by repeatedly changing the criteria for registering new cases. Furthermore, its local leaders may have exacerbated the situation by stalled information regarding the novel coronavirus and threatening doctors with the fear of being disciplined from above.

China’s early detection and warning system for outbreaks and its CDC failed to prevent SARS-like incidents from recurring, depicting a pattern too familiar where early warnings were missed. China actively hid the initial stages of 2003 SARS where again local authorities deliberately suppressed early reports on the unknown virus, under-reported cases, denied information of human-to-human transmission, detained whistleblowers, delayed reporting to the WHO, and classified the virus health report as top secret.

Another autocracy, Saudi Arabia on the face of the MERS outbreak since 11 September 2012 also delayed reporting to the WHO till 22 September. With the first notification of a novel virus from a report from Dr. Ali Mohamed Zaki, published on ProMED-mail on 20 September 2012 was the first notification of a novel infectious disease in Saudi Arabia while there were no official reports from the Saudi’s Ministry of Health (MOH). Investigations revealed that there were serious disagreements between public health authorities and scientists about the virus’ discovery with the government knowing of the existence of MERS-CoV until later; health officials being fully aware of the virus after the publication on ProMED-mail while some stated that Dr. Zaki had indeed shared the information through the internal Saudi channels well before the information appeared on ProMED-mail, but that his messages had been ignored by the MOH.

Perhaps if China were more democratic with a free media and space for whistleblowers in informing the government and the world of a strange viral outbreak, the first few cases of infections could have triggered an early response in preventing a full-blown pandemic. For in democracies such crises could have been prevented with democratic institutions, the tradition of free speech, media independence, and whistleblowers could have raised an alarm before it went out of hand.

Perhaps if China were more democratic with a free media and space for whistleblowers in informing the government and the world of a strange viral outbreak, the first few cases of infections could have triggered an early response in preventing a full-blown pandemic. For in democracies such crises could have been prevented with democratic institutions, the tradition of free speech, media independence, and whistleblowers could have raised an alarm before it went out of hand.

Interestingly outbreaks and even pandemics that occurred in democracies demonstrated open information channels, early responses, and citizen-centered approaches.

The slow response to the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in many of the Western African countries including Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone led to its spread infecting more than 28,000 and killing over 11,000. But Nigeria’s rapid action made it a poster boy of effective state public health responsiveness. While the first case of Ebola was reported in Lagos on 20 July 2014, the spread was halted in its tracks by 5 September 2014. This piece of world-class epidemiological detective feat was attributed to Nigeria’s success of early response to the virus through thorough contact tracing, monitoring and rapidly isolating potential contacts because a city of 21 million could have posed a high risk of spread to the rest of Africa and globally too.

During the Nipah virus outbreak on 2 May 2018 in India, the government of Kerala responded very similarly to Nigeria with aggressive contact tracing, isolating cases and making public announcements to reduce the spread. After the case was reported with his family member within weeks also testing positive for the Nipah Virus infection, brought forth a precise response. With a strong political commitment response components included but were not limited to activation of the command center, epidemiological investigation, notification to the central government, isolation and treatment in designated centers, intensive contact tracking, disseminating information to community, regulating social media, equipping health workforce, ensuring essential medicines and personal protective gears, safe burial practices, food and livelihood support along with psychosocial counselling to affected families. On 25 May, Kerala’s Health Department shared information with the WHO and the outbreak was declared over by 10 June with only 17 deaths and over 2000 people quarantined in two districts.

The H1N1 Swine Flu originated from Mexico in January 2009 after which it spread to the U.S. on 18 April. When cases appeared in Mexico City in March 2009, Mexico immediately notified the U.S. and WHO, effectively shutting down Mexico City within days. The Mexican government responded with transparency even though officials feared public panic and economic downturn. Although the virus was detected early, Mexico followed up with accurately reporting infection data and launching massive public awareness campaigns to empower citizens. Simultaneously, another instrumental reason for the containment of H1N1 deaths that a seasonal flu normally inflicts on the country was Mexico’s cooperation with the United States and Canada forming a public health communication network. The open information and cooperation responses for the novel viruses between the states were far more easier due to their democratic systems of network sharing. However, containment was still a challenge due to the lack of state-preparedness, eventually making it a global pandemic.

The Zika outbreak in Brazil was a delayed epidemic making it hard to identify and track as it seemed like a milder version of dengue but only became traceable when big clusters appeared. Brazilians registered 2,464 microcephaly cases between 2000-2014, and was still considered a benign disease until October 2015. On 12 November 2015, Brazil discovered a sudden surge of newborn babies with microcephaly and other neurological disorders in the northeastern area and the Ministry of Health immediately issued a public health emergency and created new public health event responses. With the WHO following suit in February 2016, information was made available and shared with the international community as well as demonstrating democracies were able to act efficiently despite the many protocols. Although Brazil still faces logistic and financial challenges in tracing the infected and paying for the operations, the government does get criticised by Brazilian legal institutions.

As now countries trade blame and keep spreading conspiracy theories on who invented or spread Covid-19, there are a few takeaways from looking at it from only an information flow perspective in democracies and autocracies. The Chinese Communist Party’s disinformation operations is still aimed at controlling the narrative and has been compared historically with Russian disinformation strategy of spreading chaos and confusion, observers label it as infodemics.

The real issue is, however, that authoritarian states are deeply threatened by an open information environment and fear losing their legitimacy and so they use their information environment to control the narrative and go as far as they can in silencing dissent. Thus, they fervently defend and control their information environment, which also includes suppressing liberal ideas and information in order to discredit alternative systems of government.

While authoritarian regimes may show how well their governance systems contain a pandemic, the world may not know how many lives could have been saved if nations embraced an open information environment to quickly detect and prevent a viral outbreak. Liberal values that do not force whistleblowers to stay silent, as well as a commitment to transparency and collaboration, has been shown to respond openly and quite quickly to such a disease outbreak. With no country immune to the risk of a communicable disease outbreak, the rapid case identification and forceful interventions can stop transmission, and for that democracies are more equipped with open information channels, independent media, and higher levels of public participation.

About the authors

Dharish David is an associate faculty for the University of London at the Singapore Institute of Management – Global Education (SIM-GE), teaching courses relating to political economy

Connie Ngo, Undergraduate Student in International Relations at the University of London, Singapore Institute of Management – Global Education (SIM-GE)

Jia Ming Ow, Undergraduate Student in Economics and Politics at the University of London, Singapore Institute of Management – Global Education (SIM-GE)