Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen has done everything in his power to suppress any sign of opposition to his rule, which has now lasted for close to four decades. The Japan-based LINE communications app must not allow itself to be used as part of the dictator’s toolkit of repression.

Besides straightforward physical elimination or imprisonment or various forms of political harassment the prime minister resorts to financial persecution leading to direct expropriation of personal property to try to quash any risk of Cambodia’s democratic opposition renewing its challenge to his dictatorship. The private property concerned is the headquarters of the peaceful opposition party the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), which was dissolved by the government-controlled supreme court in November 2017.

Until it was seized by the government In 2018 and sold by the authorities to a third party for $1.6 million a few months ago, this property was owned equally by my wife Saumura Tioulong, who is a former deputy governor of the Cambodian central bank, and myself.

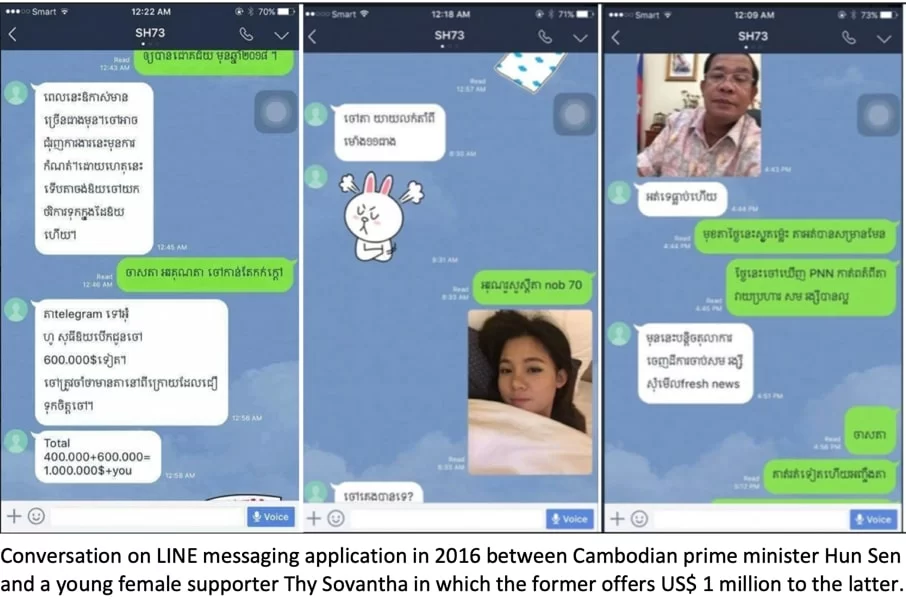

As I explained in The Geopolitics in January 2022, the property was seized and forcibly sold as part of a dispute over what Hun Sen claims is defamation by myself in a lawsuit he filed in 2017. I have previously said and maintain that Hun Sen paid a bribe of $1 million to Thy Sovantha, at the time an attractive 21-year-old female supporter of CNRP and social media “celebrity”, to switch sides and attack the opposition.

In the lawsuit Hun Sen had claimed damages and interest of $1 million, which is astronomical in Cambodia where the average salary is less than $200 a month. This is just a cynical attempt on the part of Hun Sen to match the sum he really did pay to Thy Sovantha.

The politically subservient courts have ruled that I did defame Hun Sen, despite a batch of 400 messages sent via LINE which substantiate my claims. The leaked messages can be seen here.

Hun Sen now says that the property has been sold off to pay fines for “defamation” totaling up to $2 million imposed on me by the politically controlled courts and related to several defamation lawsuits filed by other government officials on top of his own. Using the fines as a means to intimidate others into silence, Hun Sen warned on December 22 that anyone in Cambodia who supports me will face more legal action.

The dispute gives LINE a chance to strengthen the protection of its users and prevent arbitrary government punishment. It can do so by confirming the veracity of these messages exchanged between Hun Sen and Thy Sovantha.

The house is our only property in Cambodia and we plan to return to live there when my forced exile is ended by the government. A detail which Hun Sen is ignoring is that my wife, who is a French citizen, has not been cited at any stage of any defamation dispute. There is therefore no legal justification, nor even any pretence of a justification, for seizing her share of the property. Hun Sen has simply seized private property because it is politically expedient to do so.

Financial Repression

Hun Sen fears opposition from any source. I have lost count of the number of trials that have taken place against me and the years in prison to which I have been sentenced. I know that my countless convictions possibly add up to one hundred years in prison. If there was a Guinness book of records title for the most years in prison for a political opponent, I might claim it.

Any Cambodian who expresses opposition is a target for intimidation, and so are their families. The prime minister in December visited Europe where, as usual, members of the Cambodian diaspora turned out to protest against his regime. Hun Sen openly told his security services to photograph everyone who turned up, and make sure their families in Cambodia get a police visit.

Breaking the opposition in financial terms is an established part of Hun Sen’s strategy. Son Chhay, a leading opposition figure, was ordered to pay the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) $750,000 in October 2022 because of his comments that local commune elections in June were rigged. All independent observers would acknowledge this given the countless irregularities reported nationwide at all the successive elections held in Cambodia over the last 25 years. But Hun Sen recently decided to double down by asking Son Chhay to pay him an additional sum of $300,000.

The opposition was allowed to compete in the local elections in the shape of the Candlelight Party, but the exercise was deeply flawed. The widespread intimidation of opposition candidates and supporters, and the secrecy of the vote-counting process, meant that the ruling Cambodian People’s Party was free to announce whatever result it pleased. No independent observer believes that the elections were free and fair.

The ruling party can essentially do whatever it likes in the Cambodian courts which are universally acknowledged as among the least independent anywhere in the world. Courts in free, democratic countries are another matter. Hun Sen in August 2019 sued me in the courts in France, where I live in exile, because I had stated that he was behind the deaths of Cambodian trade union leader Chea Vichea in 2004 and former police chief Hok Lundy in 2008.

The French court in October found that my allegations were made in good faith as “part of a major general-interest debate over respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms in Cambodia” and rejected Hun Sen’s defamation case, in which he vainly sought a symbolic one euro in damages. The freedom of expression which the French court stressed is alien to Hun Sen, who has banned it from his political vocabulary.

Son Chhay has asked why the ruling party does not request a similar nominal amount in the Cambodian courts if the aim is simply to protect the “honour” of the CPP. The reason is that in Son Chhay’s case, as in that of Saumura Tioulong and myself in Cambodia, honour has nothing to do with it. The aim in these cases is the financial emasculation of the democratic opposition which, in national and local elections in 2013 and 2017 respectively, won nearly half of the popular vote. In the Thy Sovantha bribery case, LINE can help establish the facts in a controversy of major public interest to Cambodians and those who value democracy everywhere.

[Header image: Line Corporation, Public Domain]

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

Sam Rainsy, Cambodia’s finance minister from 1993 to 1994, is the co-founder and acting leader of the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP).