While the COVID-19 crisis first hit China and then reverberated like a shock wave around the world, Japan decided to break its supply chain dependence on China. Is this a tactic to harmonize itself with its American ally, or simply a strategic necessity?

The answer is far from simple, nor is it as straightforward as it seems. Considering its Confucian tradition of finding the middle ground, the Empire of the Rising Sun is working on both sides of the street, careful not to let the dogs of war loose.

On the one hand, Japan wants to please its unpredictable American ally, despite knowing full well it cannot entirely rely on them. The U.S. is one of Japan’s largest trade partners ($140.4 billion or 19.9 percent of total Japanese exports in 2018); thus, treading carefully to avoid an economic catastrophe is a must. Not to mention, Japan needs the American umbrella to ensure protection from its two significant threats in the region: North Korea, which regularly launches missiles into the Sea of Japan and, China, which continues to defy Japan in the East China Sea over the Senkaku Islands.

On the other hand, reducing (in whole or in part) its supply chain dependency on China is, in the current context of recession and pandemic, a strategic necessity but with a steep cost. China will certainly not accept this dissolution easily and will lash out, as it usually does, when it is disturbed. Japan is tiptoeing through a minefield and needs only to look at what is occurring in Australia since it called for a coronavirus probe and the ensuing trade war with China. Retaliation will soon be felt.

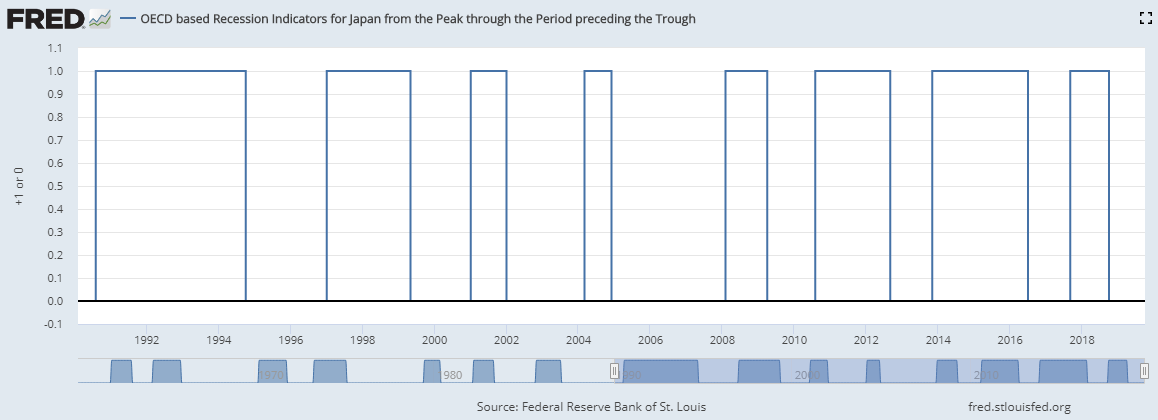

Walking a fine line between the U.S. and China, fully aware of this delicate state of affairs, Prime Minister Abe-san, like President Trump, wants to ‘Make Japan Great Again.’ Shinzō Abe plays on the nationalist and populist chord in an oft-futile effort to extract Japan from the recessionary quicksand it perpetually finds itself in (its ninth recession in three decades beginning with the Lost Decade).

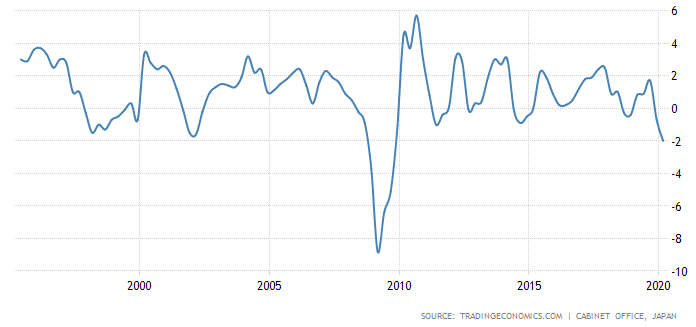

Japan lacks a long-term strategic vision and looks to treat the symptoms, once again, instead of attacking the root cause of its ills. The country has been pursuing this pattern, albeit using different tactics (e.g., Abenomics 1.0 & 2.0) yet making mistake after mistake for three decades now without any significant results. This symptom treating has not allowed the country’s economy to truly expand, as shown by the GDP Annual Growth Rate; the post-war economic model of development that created the Japanese model is clearly no longer working.

Japan’s problems largely stem from its political, economic, and social spheres that are interdependent. Firstly and briefly, at the political level, political governance is in crisis. The ruling Conservative right-wing party, Jimintō, has dominated the Japanese political landscape since 1955. The lack of political renewal means that the system is self-duplicating and stagnating. Conservative characteristics such as risk aversion and resistance to change have done nothing to help the country enjoy a healthy political landscape, especially since the country appears to be under the rule of a one-party regime in the form of a flawed democracy.

Secondly, at the economic level, historically speaking, one of the fatal mistakes of Japanese companies has been to outsource entire parts of their supply chain to China (among other countries) to overcome the 1990’s economic crisis. The idea of cutting costs has gained a foothold in Japan, creating an addiction to cheap labor and weakening the Keiretsus; the backbone of the post-war Japanese economy. Japanese companies that were synonymous for quality and innovation have lost this distinctive status while their competitors (e.g., South Koreans) have gained recognition for it. Furthermore, the Central Bank of Japan had also committed a number of errors, most notably in its management of the real estate crisis during the Lost Decade and, later in 2018, when it started ‘‘muddying its commitment to easy monetary policy’’. Taking all this into consideration, Japan’s economy, being export-dependent, is directly and severely hit when there is a worldwide economic downturn, as is the case with the COVID-19 pandemic – the result is the current recession.

Thirdly, at the social level, Japan is facing an aging declining population: ‘‘Japan’s population began to decline in 2011. The nation’s birthrate is at its lowest since 1899, with fewer babies being born each year than the previous year,’’ as presented by World Population Review. Turning to very controlled immigration after centuries of isolation such as the Japanese diaspora considered as an ‘ethnic anomaly’ or using foreigners that risk being overworked to death has not solved the problem. The absence of a sufficient working population in a position to support the country’s economy has worsened due to an increase in poverty and an education system that has been on the wane of late – all this is a deadly Molotov cocktail recipe waiting to imminently explode.

So, what can Japan do to get out of this persistent political-economic-socio-structural crisis?

The $2.2 trillion package to stimulate the economy is a first step in the right direction to help and reassure the population, but it is not enough. The Abe administration must face this crisis and pull the wool from its eyes. Additional, more radical actions must be taken to heal the country and bring it back to the world stage.

At the national level, a total reorganization of the political sphere must be done in order 1) to allow the other political parties to participate fully in the political life of the country, and 2) have a more varied representation to avoid falling into the pitfalls of Chinese-style one-party authoritarianism or American-style bi-partisanship. Food self-sufficiency requires drastic action, especially after the alarming 2018 record drop in wheat production. Similarly, the development of ecotourism is essential to stimulate the hinterland, which is dying quietly, at the same rate as its population. It must be a priority for the government. Japanese society will also have to review the status of women and their roles in the social and economic structure. Womenomics (measures initiated by Shinzō Abe to empower women economically) must be supported by a major overhaul of the childcare system, incentives to have children, and the development of infrastructure to support families. Companies also have their role to play in this matter; they must review their management methods to update their policies and offer a socio-economic model adapted to 21st century reality.

At the international level, a redefinition of Japan’s political role on the global scene is essential. Military spending has known a straight-eight-year-in-a-row rise under the Abe administration, culminating with a $48.5 billion defense budget for 2020. Militarization is a bad idea, or at the very least, an idea that should be seriously and cautiously reconsidered due to the lingering World War II memories of Japan’s brutal invasions of many neighboring countries. Restoring its damaged image is still difficult, despite Japan having invested in improving it over the years by playing the development card. Japan should also be reviewing its relations with the U.S., whether President Trump is reelected or not. If he is, then maintaining their relationship at minimum should be the policy, without alienating its ally. If he is not, waiting to see who will be the next President and what his/her actions will be before making a move is what caution dictates. Finally, Japan must be focused on maintaining good neighborly relations with South Korea and especially China, as each needs the other.

The future of Japan is intimately linked to and dependent upon its neighbors, notably China, and this is something Japan must address pragmatically. The center of gravity of Japan’s economic future lies in the core of Confucian and Asian countries, which have become the planet’s centers of growth.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

Dr Fatima-Zohra Er-Rafia is a lecturer at HEC Montréal and Polytechnique Montréal, a consultant, and an independent researcher. She holds a PhD in Business Administration with a focus on China and Japan. Dr Er-Rafia specializes in international affairs, geopolitics, cross-cultural management, and strategy. Her focus is on Weberian sociology, politics, economics, and history, and she uses aspects of all these disciplines to study Asia. Dr Er-Rafia previously served as a Corporate Strategist at Desjardins Group and as a Management Consultant, Director of Operations, and a Strategy and Business Development Consultant at Stratégies Internationales. She provides training for Business Executives at the international level and regularly gives presentations about Asia’s geopolitics, and its business, management, and culture. She is the recipient of several honors and awards and author of two book chapters on China and Japan, several articles and business case studies. For more info: www.fatimaerrafia.com